Arnold's Trail

If you were asked, "Who was Benedict

Arnold?" your answer would be, "He was a traitor." The perfidy

of Arnold, the traitor, has blotted out all memory of Arnold,

the patriot; yet patriot he once was and model soldier. As an

able leader he stood high in Washington's esteem.

In 1775 Washington appointed Arnold

commander of an expedition against Quebec. He advanced by way of

the Kennebec River over the mountains of Maine, with a force of

eleven hundred men. These men were hunters and Indian fighters.

They knew how to procure food from the forests and fish from the

rivers and how to manage birch bark canoes. Their clothes were

made of deer skins. Each man carried a rifle, a long knife, a

small axe and a tomahawk.

They assembled at Prospect Hills, Mass., September 11th, 1775,

and sailed from Newburyport on the Merrimac River, on the

afternoon of September 19th, 1775. There were ten schooners and

sloops. After a smooth voyage, they entered the mouth of the

Kennebec one morning a little after sunrise.

Arnold worked his way four miles upriver

to Parker's Flat, where his vessel anchored for a few hours.

Then lie proceeded six miles up the river. Making its way among

rocks, islands and bays the fleet became scattered. Sailing

through Merrymeeting Bay, they pushed on toward Gardinerstown,

arriving Friday, September 22d. Arnold halted there to obtain

bateaux from Major Reuben Colburn's ship-yard.

Washington had ordered the building of

two hundred four-oared bateaux, each to be equipped with two

paddles and two setting poles. The bateaux were quickly but not

well made, as they were to be abandoned within a few weeks and

the need of staunch boats was not appreciated.

Major Colburn had been ordered by

Washington to send scouts over the route. Dennis Getchell and

Samuel Berry of Vassalboro performed this service. They reported

to Arnold that his advance was being watched by Indian spies

employed by Governor Carleton. Yet the expedition proceeded and

farther up the river Arnold was told by a squaw that at

Shettican the Mohawks were ready to destroy them.

When shoal water was reached they

transferred to the bateaux and thus moved on toward Fort Western

in the Augusta of today, the Hallo well of 1775, the Cushnoc of

Indian geography, forty-three miles from the sea. The whole of

Arnold's army arrived there before Sunday, September 24th.

Aaron Burr, afterward Vice-President of

the United States, was a private in this expedition. At Fort

Western he met Jacataqua, a beautiful princess of the Abnaki

tribe, who was eager to go with the soldiers to Quebec.

Before leaving the Fort a great feast

was spread. Jacataqua and Aaron Burr had killed a bear and two

cubs in Captain Howard's cornfield and these were roasted for

the banquet. Around them were arranged ten baskets of roasted

ears of corn with quantities of pork, bread and potatoes, one

hundred pumpkin pies, watermelons and wild cherries. William

Gardiner of Cobbosseecontee, Major Colburn and Squire Oakman of

Gardinerstown, Judge Bowman, Colonel Cushing, Captain Goodwin

and Squire Bridge of Pownalborough, with their ladies, were

invited guests. Led by the company officers, the troops and

guests marched to the table. Judge Howard was at the head of the

table, Jacataqua on his right and Aaron Burr on his left, with

General Arnold at the foot. Reverend Samuel Spring asked the

blessing, praying that Jacataqua might influence her people of

the wilderness to give them safe conduct along the march.

Later this maiden, being a great

huntress, scoured the forests for food for the starving

soldiers. Skilled in the use of herbs and roots, she faithfully

nursed those who fell ill.

On resuming the journey the troops found

the river half a mile beyond Fort Western blocked by the falls.

On the east side was a seldom travelled road to Fort Halifax,

and over this the country people with their oxen and horses

carried the bateaux and stores to Fort Halifax.

From this point part of the force

proceeded by water, the remainder by land. Half a mile above

Fort Halifax, they came to the first carry around Ticonic Falls.

This was accomplished by hard labor. A little beyond came the

dangerous Five Miles Ripples. Then the expedition reached

Canaan, now Skowhegan, where they had dinner. Next came a battle

with the Skowhegan falls. Here, between two ledges, forming a

passage only twenty-five feet wide, the river drives like a mill

race. With difficulty the bateaux were hauled through this

gate-way. On the succeeding long run of swift current, the men

walked on the banks drawing the boats by the painters, while

others pulled them from the rocks. Then they came to another

fall twenty-two feet high, which they passed with difficulty.

The troops were very tired and very glad

when they reached Norridgewock. They remained there a week to

repair the boats and refit the expedition.

Carratunk was the entrance to the real

wilderness. Arnold reached the Great Carrying place there

October 11th, the army in good health and spirits. Rain set in.

Because of inadequate shelter some few were taken ill and by

Arnold's direction a hospital was built which was immediately

occupied by Dr. Irvin with his patients.

Resuming the journey, Arnold wrote

Washington the greatest difficulties were passed and he hoped to

reach the Chaudiere in eight or ten days. The difficulties of

the road increased this time, somewhat.

Arnold entrusted to two Indians a letter

to John Manier, or Captain William Gregory or Mr. John Maynard,

Quebec, saying that he was on Dead River, one hundred and sixty

miles from Quebec, with about two thousand men, and that he

designed to cooperate with General Schuyler and assist the

Canadians in resisting Great Britain's unjust measures. The

letter asked the number of troops and vessels at Quebec.

Enclosed was a letter to General Schuyler asking for advices

from him. The letter fell into the hands of the

Lieutenant-Governor of Canada. This was the first they knew of

Arnold's detachment.

Eight miles from Bog Brook the

expedition came to Hurricane Falls, and another carry. A few

miles beyond in a clearing stood the cabin of Natanis, the

Indian, where is now the village of Flagstaff. The store of

provisions being very low, all men unfit for duty were sent

back.

October 19th rain began, resulting in a

disastrous flood. Dead River which drains many ponds suddenly

swelled. In nine hours it rose eight feet. At four o 'clock,

when Arnold and his party awoke, they found their baggage in the

flood.

|

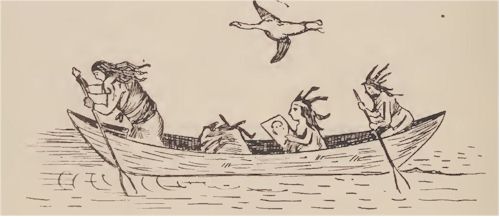

| The Flight of Nitanis |

Part of a Letter in the Indian Picture

Writing on Birch Bark, supposed to have been written by the

Norridgewock chief, Nitanis, informing his clansman of his

escape from the perils of Arnold's expedition against Quebec,

October, 1775. It was found in an Indian trail, in the

wilderness of the Upper Kennebec.

The weather grew cold and the soldiers

had no protection but tree boughs. Many boats were under water

and the landmarks were altered. Soldiers by land or water fared

hard, yet they pushed on to Black Cap rapids and the next

carrying place, Ledge Falls.

The next obstruction was Upper Shadagee

Falls, a sharp pitch followed by a long stretch of swift water.

Here the river makes a double turn around the cliff. In passing

this five or six bateaux filled and sank. Near the Falls Arnold

camped for the night and the next day resumed the journey. On

October 24th, he came to Serampos Falls, where he spent the

night. It rained and snowed, but they went on, resolved to

perish rather than give up the expedition.

They now passed into Chain of Ponds,

Long, Natanis and Round, from the last of which they were

puzzled to find an exit, but finally discovered one in Horse

Shoe Stream.

They were forced to halt and when they

lay down to sleep knew not whether they were on the right or

wrong way. In the morning no easy portage could be found, yet

they moved on, carrying from pond to lake, till the shaky boats

were placed in Moosehorn or Arnold, largest and most beautiful

of all the ponds in that region.

Now began the long portage over the

height of land. They encamped in the meadows, by Arnold's River,

to wait for the rear division of the army.

The report reached them that the

Canadians would supply them with food and that there were few

regulars at Quebec to resist them.

After issuing a note of cheer and

instruction to his men, Arnold rode three miles farther to a

house of bark on the eastern shore of Lake Megantic and encamped

for the night. Next morning he set out with four bateaux and a

birch bark canoe, for the outlet of the lake, the Chaudiere

River, a boiling, foaming stream.

There Arnold's party was in great

danger. Only the best boats could defy the water and avoid the

rocks. Two boats were destroyed and three others damaged but no

lives lost. At Sertegan, provisions awaited them. The people

showed good will and admiration for the courage of the

Americans. It was hard to find lodging. Huts were put up and

fires built, but the soldiers were very uncomfortable; for the

weather was cold and it snowed all day and night.

|

Second Company, Governor's Foot

Guard,

of New Haven, Conn. |

On August 18th, 1912, The Second

Company, Governor's Foot Guard, of New Haven, Conn., founded in

1774, and one of the most famous military organizations in

America, started a pilgrimage to Quebec, following the route

through Maine, taken by Benedict Arnold on his famous expedition

to Canada. An incident of this pilgrimage was the dedication of

a boulder monument at Fort Western, Augusta, where 137 years

before, Arnold's forces halted for a week on their memorable

march. The boulder was erected to the memory of the Connecticut

men who followed Arnold to Canada. The above picture was taken

at Augusta, on that memorable occasion. Fort Western is seen at

the left of the picture.

Arnold's messenger was captured. Then

came rumors that the approach of the Provincials was known to

the enemy; that the river was guarded by a frigate and a sloop

of war, and that the inhabitants in the vicinity of Quebec had

been summoned to the defense of the city under the penalty of

death.

Still Arnold kept at work; he collected

provisions and more boats, even made plans to scale the walls.

November 13th, in the inky blackness of night, three trips

across the river were made and five hundred men were landed on

the north side. Then the tide ebbed, exposing the rocks, and the

wind blew, preventing the crossing of more troops. The moon

appeared and the Americans on the north shore were discovered.

Arnold's venture was a failure. His march was over.

Mrs. E. C. Carll

|

![]()

![]()