General Henry Knox

Passengers on the Rockland division of

the Maine Central Railroad, passing through the quaint little

hamlet of Thomaston, may observe on the brick wall of the

railroad station, a tablet, bearing an inscription to the effect

that this structure was built by General Knox in 1793. This

building was known as the "farm house" a century and a quarter

ago, when Gen. Knox and his family lived in state at

"Montpelier," a beautiful mansion, then the pride of Thomaston.

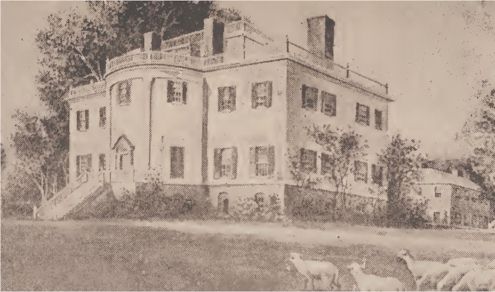

Situated on the crest of a hill near the river Georges, the

mansion commanded a fine view down to the sea. The group of

buildings was in the form of a large crescent, sloping back from

the river, the mansion in the center and nine buildings on

either side, including the farm house, stables and out

buildings. The mansion itself was a wonderful structure for

those times. It had a basement of brick and two stories built of

wood; a fourth story, a sort of cupola in the center, had a

glass roof. Double piazzas extended on all sides of the mansion.

The railings and columns enclosing these and the balconies

displayed a great deal of fine work and skillful hand-carving.

We can only imagine the original grandeur of "Montpelier,"

because many of the outward decorations had been removed before

the first picture was taken.

The interior was decorated and furnished

in a style unique for those primitive days. The wall papers

resembled tapestry. The background of the hall paper was

buff-colored. On the wall at the side of the wide stairway were

large, embossed, brown paper figures of men carrying guns. On

the library paper were pictures of ladies, reading. Here was

Gen. Knox's collection of books, nearly sixteen hundred volumes.

In the reception room, at the center of the mansion, was a

portrait of Gen. Knox by Gilbert Stuart. A part of the furniture

came from France. Mrs. Knox's piano was the first in that

region. The Knox Street of today was Gen. Knox's driveway. It

opened from Main Street by a large gate surmounted by a carved

figure of the American eagle.

|

"Montpelier, "

General Knox's Home in Thomaston |

IGen. Knox moved his family to

"Montpelier" from Philadelphia in June, 1795. On July 4th, the

doors of the mansion were opened wide that all who wished might

meet the famous general, and view the splendors of his new and

elegant home. His coming wrought much of change in the quiet

life of Thomaston. "Montpelier" came to be noted for its lavish

hospitality.

"Oh, welcome was the silken garb, but

welcome was the blouse.

When Knox was lord of half of Maine and

kept an open house."

General Knox had for his guests the

entire tribe of Tarratine or Penobscot Indians, who enjoyed

their visit and the bountiful repasts provided for them so well

that they stayed for weeks. Indeed, they did not seem to think

of going home at all, until the General said to the chief, "Now

we have had a good visit and you had better go home."

Gen. Knox's estate included the greater

part of what was known as the Waldo patent, originally the

property of Mrs. Knox's grandfather, Gen. Samuel Waldo of

Massachusetts. This land, lying between the Penobscot and

Kennebec Rivers, included nearly all of what is now comprised in

the counties of Knox, Waldo, Penobscot and Lincoln. Gen. Knox

had come into possession of this vast territory, partly through

his wife's inheritance and partly by purchase. He planned to

live here and develop the natural resources.

He began at once to set up saw-mills,

lime-kilns, marble quarries and brick yards; he also constructed

vessels, locks and dams. He converted Brigadier's Island into a

stock farm, where he kept cattle and sheep imported from other

countries. All these various enterprises gave employment to a

large number of workmen, and caused a boom in the trade and

commerce of Thomaston.

Although Gen. Knox was a fine soldier

and had proved himself well versed in military tactics, he was

without experience in any of the industries in which he now

engaged. Disputes about the boundaries of the islands in the

Waldo patent caused him to enter into costly lawsuits. The

expense of carrying on so many kinds of business proved too

heavy a drain on his resources and he became deeply involved in

debt. Had he lived longer, he might have been able to overcome

his financial difficulties, but that was not to be.

One day while eating dinner, he happened

to swallow a small, sharp piece of chicken-bone. This lodged in

such a manner as to cause him great suffering, ending in his

death on October 25, 1806, at the age of fifty-six years.

Mrs. Knox spent her remaining years

quietly at "Montpelier." As there were no funds available for

repairs, the mansion gradually lost much of its former glory.

After the death of Mrs. Knox in 1824, the estate was for several

years in the hands of different members of the family.

"When the Knox & Lincoln Railroad was

built in 1871, it passed between the mansion and the servants'

quarters. The mansion was then sold for $4,000 and torn down.

The executor tried to sell to someone who would preserve it, but

no one seemed to consider the historical value of the place.

Of course, we are interested to learn

where Gen. Knox lived when he was a boy and something of his

life during the years given to his country's service. In his

boyhood Henry Knox lived with his parents on Sea Street in

Boston. He was fond of outdoor sports and was frequently chosen

as leader by his playmates. But his school days were soon over.

When he was twelve years old his father died, and Henry took

upon himself the support of his mother and younger brother. He

left the grammar school and went to work in a book store. His

education did not end, however, for he studied by himself at odd

moments from the books at the store. He was much interested in

military matters and his studies were chiefly along that line.

He learned to speak and write the French language, an

accomplishment which proved useful in later years, when he came

to meet Lafayette and other French generals of our ally across

the water. He also took time for thorough drill in a military

company.

When he was twenty-one years old, Henry

Knox went into business for himself, opening "The Lon-don

Book-Store" in Cornhill, Boston. Later he added book-binding to

his business.

He had been in business only a few years

when he felt that his country needed him and he did not hesitate

to offer himself. A watch had been kept on the movements of Knox

and of others who were known to be in sympathy with the

colonists, and they were forbidden to leave the city. But, on

the night of April 19, 1775, Knox disguised himself, and,

accompanied by his wife, quietly left his home. Mrs. Knox had

his sword concealed in the lining of her cloak. Knox went to the

headquarters of Gen. Artemus Ward in Cambridge and volunteered

his services.

One of his first assignments was to help

in preparing for the siege of Boston. More siege guns were

urgently needed but there seemed to be no way of procuring them.

An idea came to the resourceful mind of Knox. Our forces under

Ethan Allen had taken possession of a large supply of ordnance

at Fort Ticonderoga captured May 10, 1775. Knox's idea was to

transport that artillery, by the crude methods of those times,

hundreds of miles across lakes, rivers and mountain ranges from

Ticonderoga to the Heights of Dorchester. After thinking it over

carefully Gen. Washington gave his consent to the plan.

Knox carried the undertaking to a

successful conclusion and arrived in camp with the guns early in

February. With this reinforcement of artillery, it did not take

long for our army to persuade the British that Boston was too

hot a place for them. On March 17, 1776, the British general,

Howe, and his troops sailed away to Halifax.

On Nov. 17, 1775, Congress gave to Henry

Knox the rank of Colonel and appointed him chief of the

artillery of the army. His commission did not reach him,

however, until after his return from Ticonderoga.

We hear of Col. Knox again and again and

always as pushing forward. He encouraged the hardy soldiers on

that bleak and stormy Christmas night when they were crossing

the Delaware River amid cakes of floating ice, while hailstones

beat upon their backs. Gen. Washington gave much credit to Col.

Knox for the victory won by our troops at Trenton the next day,

Dec. 26, 1776. He was now made a brigadier-general, with the

entire command of the artillery.

After the surrender of Cornwallis at

Yorktown, October 19, 1781, Gen. Washington complimented Gen.

Knox on his skill in handling the artillery. On the

recommendation of Gen. Washington, Knox was promoted to the rank

of major-general dating from November 15, 1781.

The war over, Gen. Knox returned to

Boston. On March 8, 1785, he was elected by Congress to fill the

office of Secretary of War. Secretary Knox and his family moved,

soon after, to New York, at that time the seat of the national

government.

In 1789, President Washington

reappointed Knox to the office of Secretary of War. The

management of the army, the navy, then in its beginning, and

Indian affairs, were all in the hands of Secretary Knox. He

influenced Congress to order the building of six frigates, the

keels of which were laid during his term of office. One of these

was the ''Constitution'' or ''Old Ironsides.''

After having served his country

faithfully for nearly twenty years, Secretary Knox decided to

withdraw from public life and devote himself to his family. He

resigned at the close of the year 1794. Before this he had

ordered the building of an elegant mansion on his estate in the

District of Maine, to which, as we have said, he moved his

family in 1795.

Mrs. John O. Widber

|

![]()

![]()