When Jean Vincent Followed the Trail

In 5 short Chapters

Chapter I

Many years ago in the year 1652, a little boy was born in Oleron,

France. His mother died when he was less than two years old. His

father was a rich and powerful baron of the land. He owned many

houses scattered through the provinces near the Pyrenees

Mountains. He was not an unkind father, but he was always too

busy to spend any time with his children, so he left them to the

care of servants, nurses and the Jesuit Priests.

When this boy was very little, he

trotted about the castle after his older sister and watched the

women embroider and weave by hand yards and yards of glistening

silk made from the worms that fed on the mulberry trees which

grew around the castle grounds. As he grew to be older, that was

too tame a life for him, so with his older brother, he rode on

his spirited little pony, a falcon on his wrist and half a dozen

dogs barking at his heels. He even followed the hounds and saw

them kill the wild boar, whose fierce tusks gored the dogs as

they pulled him down. In the evening, when the lords and barons

joined his father at supper, he was allowed to remain and toss

off his glass of wine and give his toast to the fair ladies

present, as if he were grown up.

Once his father took him to Paris, where

reigned one of the most powerful monarchs of all Europe, King

Louis XIV. Jean Vincent, for that was the little boy's name, was

dressed in his best doublet or jacket of blue velvet, slashed on

the sleeves, with white satin puffs showing through the slashes.

His trousers were velvet, too, and he wore white silk stockings

and pointed leather shoes with gold buckles. His hat was of felt

with a long, white ostrich feather, fastened on with another

buckle, also of gold, while lace ruffles hung over his hands, -

not much of a costume for a boy to wear to climb a tree! O, yes,

he wore a long pointed knife called a dagger or poniard, such as

a noble wore to kill if he were attacked by thieves. Often he

used it to thrust or prick a servant who did not move quickly

enough to carry out his orders.

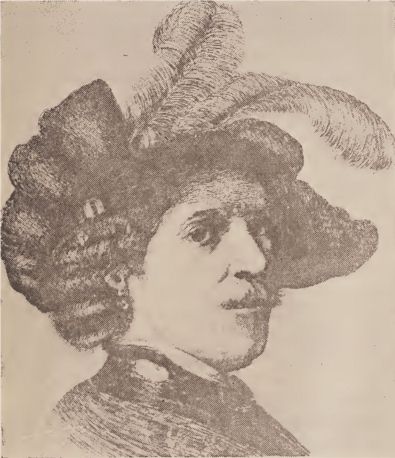

|

| Jean Vincent (The Baron Castine)

in Youth |

The King liked the looks of Jean Vincent

and told his father that when the boy was twelve, he should be

made one of the gentlemen of the court.

The next year the boy's father died. His

older brother became the baron, taking, as was the custom, all

the lands and houses. Then the sister married and most of the

gold and jewels went for her marriage dot. There seemed nothing

left for Jean Vin-cent but to go up to the Court at Versailles

and remind his Majesty, King Louis, of his promise. When he

arrived at Court, Louis XIV readily agreed to take him into his

service, saying, ''Little Jean, I will soon give you a chance to

become a great warrior in our next war with England.''

An ancient court was a bad place for a

lad of twelve, for many reasons. First, in the King's household

lived so many noble gentlemen that there was not enough work for

half of them. They spent their time playing dice, drinking,

teaching cocks to light, and ferrets to catch rats, and in doing

even worse things. Jean grew very tired of it. He wanted leather

buskins and jerkins and a good stout helmet on his head.

The French were having trouble with

their colonies in Acadia, the new world over the big ocean.

Louis and his great Cardinal decided to send one of the King's

crack regiments over seas to settle all difficulties. So the

Carignan Salieres were shipped to Quebec. Jean Vincent, though

only fourteen, belonged to that regiment. It was a beastly trip

across the ocean and even the noblemen were crowded like cattle

in the small cabins of the vessels transporting them.

While Jean Vincent had a fine swagger and felt himself every bit

as brave as the colonel, there were days when he could not lift

his head and wished himself either back at court or at the

bottom of the ocean, anything to get rid of that dreadful mal de

mer, as the French call sea sickness.

At last Jean Vincent found himself in

Quebec, glad enough to be ashore and starting real life. Like

the boys of this century, he was fascinated by pirates and the

Red Man. The lure of the wild drew him and this odd little New

World town, so like and yet so unlike the towns of his own dear

France, enticed him.

The year that followed was exciting

enough to suit him. His regiment was continual engaged in

skirmishes around Quebec. He saw the many horrors of Indian

warfare. At first, to be sure, he turned sick at the cruel

practice of scalping. A painted, half-naked Indian Chief, with

his snaky war bonnet of feathers waving down his back, was not a

pleasant sight to see standing over some poor French soldier,

especially if he raised his tomahawk to bury it in the skull of

his young victim.

Chapter II

At last the Indian trouble was settled.

The Salieres were disbanded and that was why Jean Vincent found

himself, at fifteen, left stranded in New France with little

money or train-ing for a pioneer life. In his possession was one

other asset which proved to be the very best thing in his whole

life. It was the royal grant of a considerable tract of land in

a wild country many miles south of Quebec and no way to get

there.

Other young ensigns of his regiment had

been given land nearer Quebec. In the neighborhood of the fort

where Jean Vincent lived, was a holy mission of the Jesuit

Priests. Jean had heard them talking about this settlement which

had been given him by the King. Scarcely any one lived there but

a tribe of Indians called Abenakis. Jean had often been to the

chapel to confess his sins, for he was a good Catholic.

One day in the late summer he gathered

all his belongings at the barracks and put them in a stout sea

chest which had a rude lock. He sent this over to the cabin of

Father Bigot, meaning to ask him if he would send it by the

first French ship sailing for Pentagoet. Jean, that youngest

ensign in the Salieres, was certainly good to look at, as he

stood tapping at the Jesuit's cabin door. He had the dash and

dare of youth, the '' devil-may-care" and imperious way of the

French nobility of that date. The bright uniform of the already

disbanded King's regiment gave an added glitter and authority to

his boyish figure.

At his knock the holy man opened the

door. ''Bon soir, Reverend Father," said young Jean, making the

sign of the cross as he spoke.

The priest, a man of delicate frame,

clad in a long black robe with a cord tied about his waist,

motioned for the lad to enter. Jean Vincent stood near the

table.

''Father Bigot, they tell me in the

parish of St. Anne, that you are the only one now in Quebec, who

knows about the shores of Pentagoet which is to be my new home.

I have come to ask you how I may best arrive at that

settlement."

''Be seated, my son," said the priest. ''God has directed your

footsteps here at this opportune moment. Tomorrow at dawn three

Algonquins who belong to the Abenaki tribe will start for

Pentagoet. They are Indian runners who brought messages to our

Governor that a band of the Iroquois are on the war path. I will

send a message by them commending you to their powerful chief,

Mataconando. They will also show you the way to your new

possessions.

Jean expressed his thanks and the Holy

Father continued: "My son, you are over young, yet. Carry

yourself with humility, make a good accounting to his Majesty by

the manner in which you rule your land and the savage tribe

which is settled there. See that you lead them to God."

Chapter III

The next morning, at the first cock's

crow, from the little cabin of the old Indian woman, Monique,

who lived beneath the shadow of the Jesuit mission, silently

started two stalwart Indians, followed in single file along the

trail by two lads. The younger was Jean Vincent. He wore knee

breeches of stout cloth, heavy leather gaiters with moose-hide

shoes. To be sure, a soft blue silken shirt or blouse tied by a

black kerchief was next his skin, but it was completely hidden

by a thick leathern jerkin. He was slender, about five feet nine

in height. He had good features, dark brown hair, a keen blue

eye and a laughing mouth full of strong white teeth. He appeared

to have the bright, joyous disposition usual with the French. On

his back he wore a pack done up in a blanket, an arquebuse or

old-fashioned musket was slung over his shoulder. In his belt

was a hunting knife and a small hatchet.

The lad walking behind him so silently,

was larger, a handsome Indian of seventeen. He, too, had a

pleasant mouth with big white teeth, but he marched along

without saying a word or even giving a smile. He wore a full

Indian suit of deer skin, slashed and fringed. Slung beside his

pack was a strong bow and a quiver of cruel arrows. A scalp-ing

knife was in his belt.

Only occasionally did the Indian runners

ahead turn to speak to them. Most of the conversation with Jean

Vincent was carried on by signs. They knew a few words of French

and he knew some words of the Iroquois language which they

understood. So they filed on through the Plains of Abraham until

they reached the banks of the St. Lawrence. Quietly, the head

Indian drew out his canoe from its hiding place. He motioned to

Jean Vincent to take the seat arranged for a passenger. The

others, kneeling, plied their paddles with swift, sure strokes,

until they reached Port Levis, eleven hundred yards across on

the bank opposite Quebec. They carried around the Falls of

Chaudiere which fell, one magnificent leap of 135 feet, and

began the ascent of the Chaudiere River.

The sun was bright and the September air

was fresh with tonic. Jean Vincent was enjoying the canoe ride,

but why such gloom? His companions made him weary. O, for a jest

with a fellow officer of his regiment!

About sundown, they reached a small

stream, branching from the main river, winding like a shining

snake through fields growing sere and brown. The sheltering

knoll of hemlocks and red cedars was perfect for a camping

ground. The packs were unstrapped. One of the older Indians took

out a line and fish hook which he had carved from bone, lighted

his pipe and began to smoke as he fished from a neighboring

rock. The other Red Man took two sticks which he rubbed very

briskly together and soon a tiny spark fell to the little heap

of dry pith he had gathered, and in a moment more a fire of bark

and twigs burnt merrily.

The lad had found some saplings growing

against a big boulder, facing the water. He bent these over and

fastened them for an Indian shelter called a wickie-up. He cut a

few boughs from the hemlocks and cedars and threw them into the

little hut. At first, Jean Vincent stood doing nothing, then he

began to help the boy cut boughs. When their work was done, he

pointed at the Indian boy and said to him, first in French and

then in Iroquois, ''What's your name? ''

Without a smile the older lad said, ''Wenamouet.''

''Where do you live?" ventured Jean

Vincent.

"Pentagoet," said the other.

''I like you,'' said Jean, ''and I am

going to live there, too. Please be friends with me."

To his surprise Wenamouet's features

flashed into a dazzling smile.

"I like you now. I talk little French.

Father Bigot, he told me."

Thus began their friendship.

They helped the fishermen until they had

a string of perch, which they broiled over the live coals of the

fire. Then they flung their tired bodies on the sweet hemlock

boughs. For a moment Jean Vincent watched the twinkling stars

shining between the branches of their shelter and soon was deep

in sleep.

Chapter IV

So they went on for a week or more. Up

the Chaudiere to Sartigan, from there to the Big Pond (Lake

Megantic). Partridge and game were plentiful and the rivers

teemed with fish. All three Indians knew both by instinct and

experience, where to get the best fish. The French lad was happy

in the life on the trail and friendship was slowly but surely

cementing between him and Wenamouet. The day they completed the

passage of the chain of lakes in the shadow of Mt. Bigelow

before making the trail for Dead River, Jean Vincent and

Wenamouet left the older men fishing and went deeper into the

woods to follow a red-winged blackbird and see what small game

was at hand. They had lost their trail on the border of a swampy

stretch, when a long, piercing yell sounded across the tops of

the swaying pines.

''What's that?" said Jean in a hushed voice.

''H'st!'' said Wenamouet, with his lips

close to Jean's ear, ''Iroquois war whoop. I have seen signs all

about. They trailed here today."

On their return to their camping ground,

they found it deserted, except for a broken arrow and an

Iroquois mask over which they stumbled. The mask was a strange

bit of wood neatly fitted with two halves of a copper kettle,

with two holes left for eyes. Their Indian runners had surely

been taken captive by the hostile tribe and all food, blankets,

and even the canoe had disappeared.

Two sorry lads sat among the boughs that

night, not daring to have a fire, scarcely daring to breathe.

They were on the alert at the crackling of every twig. The

forest was alive with noises. Amid the sobbing of the wind in

the branches, sounded the lonesome call of the loon in the bog.

A wolf raised his hideous voice from the fastnesses of the

mountain. Every now and then came the weird, blood-curdling

whoop of the Iroquois as they wound their way along the carry

with their sullen, half dead captives, the sound ever growling

fainter as they left the Abenaki's trail to go westward to seek

the Mohawk trail.

Toward dawn Jean fell asleep. Not for

several hours did he wake to the peaceful twitter of small birds

and the dancing sunlight through the inter-laced branches. His

young friend stood over him, gently shaking him.

''Arise, sluggard, it is time to eat,

''' said Wenamouet, pointing to a wild duck which he had just

brought from the marsh. In a moment Jean Vincent was ready to

help. They plunged the bird into the brook until its feathers

were dripping wet, then buried it in the hot coals of the fire

which the Indian boy already had made. In a short time they

pulled it out, easily skinned off the outside and the meat was

done to a turn, without scorching.

All day they wandered over the carry,

often losing the trail, then finding it again, until they

reached Dead River. The French lad had been considering all day

their dilemma. Not a sign of human habitation, no canoe, no

supply of food, no definite trail, what would become of him if

anything should happen to his young friend? Could the Indian boy

find the trail so blindly blazed?

''Wenamouet, can we ever get to

Pentagoet alone?" asked he, wistfully.

''I think I lead right," said the

Indian.

''Have you ever been over it before?"

queried Jean Vincent.

''Ninny, how come Wenamouet at Quebec?"

he answered.

''Where do we go now and how can we go

up this river, you call Dead, without a canoe?" insisted Jean.

''Indian show stupid paleface,'' laughed

the copper-colored lad. ''Come help me now," he continued, ''I

command, too. My father heap big chief, before he went to Happy

Hunting Grounds. I have right to wear eagle feathers in hair

just as much as little French lord."

He led the way into the deep woods,

where he selected six good-sized logs which were lying rotting

on the ground. They managed to drag them out, one at a time, to

the river bank. There Wenamouet cleared the decayed leaves from

the hollow inside, placed the logs together, tied them securely

with stout thongs, which he unwound from under his deerskin

hunting jacket. They made a good firm raft. With their hatchets

and hunting knives, they hurriedly shaped a passable paddle and

a pole. On this frail craft, they launched forth down the river,

Wenamouet paddling and Jean Vincent helping with the pole at all

dangerous turns. Barring an occasional upset, they made good

time in reaching ''The Forks'' where Dead River meets the

Kennebec. Here the trail divided. The Abenaki's course lay up

the river to Moosehead Lake. The trail that Benedict Arnold

covered a hundred years later was down the Kennebec.

Chapter V

After several days of paddling the raft

on the river and of nights spent in the woods along the bank,

they came to Moosehead. Jean Vincent was appalled at the thought

of venturing on the rough water with that tiny log raft. Even

the Indian boy shook his head thoughtfully when he saw the great

waves crested with foam kicked up by the October winds sweeping

over the mountain tops. Then a piece of luck came their way.

Wenamouet found, under a low spreading willow near the lake's

outlet, a good, strong canoe with two new paddles. It was the

first time Jean had seen him express any emotion. Wenamouet

began to tread the measure of an Indian dance. Clapping his

hands, he grunted, ''Ugh, my father, he ask the Great Spirit to

help his son," and he repeated some sort of prayer in a dialect

that the French boy could not follow.

With this help in a time of great need,

the two boys continued swiftly on their way. Wenamouet realized

how much more of the trail remained to be covered and he was

anxious to hasten along before November ushered in her ice and

snows. The nights were growing cold. They had but the thin

blankets about their packs.

It was a short carry from the top of

Moosehead Lake to the west Branch of the Penobscot. A long

paddle followed to Chesuncook Lake, where they were obliged to

carry at many impassable places until they came to Lake

Pemadumcook. By this time November was at hand. The nights grew

bitter and only their roaring campfires kept them from freezing.

They were now in the land of the Abenakis and were no longer

afraid of hostile tribes.

The rabbit had changed its brown coat

for its winter one of white. The squirrels and all small animals

had drawn into their winter holes. Food grew very scarce. Two

days and nights went by without a morsel of any kind to eat.

Then they found some withered acorns, so bitter, but something

to ease the gnawing pangs of their hunger. Jean Vincent was

ready to give up. Then passed two more days absolutely without

food. Wenamouet saw Jean Vincent chewing at a piece of leather

cut from his leggings. The Indian stomach is accustomed to long

winter fasts in hard years, but not so the French.

''Sacre Bleu!" said Jean in quaint

French oath, ''Wenamouet, shoot me with this arquebus as soon as

you will, but I beg of you don't scalp me."

Faint, dizzy, unable to stand or drag

one foot after the other, the boy threw himself on the ground

and began to moan in his agony. Wenamouet wanted to comfort him,

but he knew they must keep on. Death was staring them in the

face. If only they could reach some Indian village, where they

could get food and a bit of rest.

Then Wenamouet uttered a cry of glad

surprise and Jean opened his eyes to see his companion run to a

rock which showed through the light coating of snow. Wenamouet

began to peel off some moss, having a red, shell-shaped leaf,

covered with caterpillars and spiders. He took a piece of bark

and made a dish to hold water. Then, from the camp fire which he

had made to warm Jean, he took red-hot rocks and these he

dropped into the water until it boiled and from the moss and hot

water he made an insipid tasting soup, which was nourishing

enough to bring renewed life and hope to Jean.

Then Wenamouet taunted him to get the

boy's courage back, saying, ''Shall I tell the pretty squaws at

Pentagoet, that the French blackbird showed the white feather on

the Abenaki trail? Come, little brother, take heart once more

and I will tell you the story of the Great Moose."

So all the way to Mattawamkeag, the true

friend, the Indian lad, kept Jean's mind from his bodily ills by

stories of Indian lore. All the way from Quebec he had been

teaching him woodcraft, how to blaze a trail, the habits of

game, where the best fish hide, all the things the Indian learns

through his early boyhood.

At Mattawamkeag, the Sagamores of the

Indian village welcomed them with hospitality. They gave them

food and let them rest in the wigwam until their strength

returned. Wenamouet accused Jean Vincent of taking notice of the

handsome Indian girls, who wore their hair braided in a becoming

style and wore deerskin dresses, richly embroidered with

porcupine quills and shells. He confessed they did make an

attractive picture to a lad lost in the wilderness for two

months.

Straight down the grand old Penobscot,

still in their borrowed canoe, they paddled. A carry at Bangor,

a tussle with the wind and rapids at Bucksport narrows and Jean

Vincent as he came out into the glory of the broad, open bay,

felt as if he must be nearing the ocean. Wenamouet steered their

birchen craft with long, graceful strokes through the back cove

and into the narrow channel between the red-green marshes,

around the sandy point into the deep, blue harbor. Jean saw the

gently curving beach, fields sloping to the water ^s edge, a

babbling brook lined with small fruit trees, and, back against

the cool evergreens, a hill sloping each way to a white beach; a

fort, a chapel, a house or two, and here and there in quiet

domesticity, a wigwam with a thin line of smoke floating

peacefully upward.

''What place is this?'' asked Jean

Vincent.

''Pentagoet," said Wenamouet.

As Jean Vincent, Baron Castin of St.

Castin, stepped from the canoe to the beach, hope and happiness

filled his boyish soul with a sweet content.

How he ruled his Abenakis, how he gained

a wife and what befell his friend Wenamouet is a story that has

already been twice told.

Louise Wheeler Bartlett

|

![]()

![]()