Maine's First Christmas Observance

Did you know that the very first

Christmas observance in New England, if not the first in our

country, was in Maine? It was on a desolate little island at the

mouth of the St. Croix River, about sixteen miles below Calais,

called "The Isle of the Holy Cross" by the adventurous little

band who had settled there.

You have read all about the first

Thanksgiving day, appointed by Gov. Bradford to celebrate the

first successful harvest of the Colonists on the Ply-mouth

shore; but our school histories have nothing to say about the

first Christmas, celebrated, not by the Massachusetts colonists,

who did not approve of Christmas merry-makings, but by a little

band of Frenchmen, headed by DeMonts and Champlain, six-teen

years before the coming of the Pilgrims. We may feel sure that

this was the first Christmas celebration, for it was the first

settlement attempted by white men, even for a few months, on our

shores.

The Maine Christmas of 1604 was as

different as possible from the Christmas days you know. To begin

with, there were no women or children to take part in the

festivities and what is Christmas without the little folks!

There was no. Christmas tree, although trees were the most

abundant things the island afforded and easily could have been

cut but what would have been the use of a tree when they had no

presents to hang on it and no children to admire and exclaim

over it? The usual Christmas dainties were lacking, too, as you

might expect, where men must do all the cooking and there were

no shops from which to purchase supplies. Yet we read that they

had a feast and you who know the delicious taste of a roast

haunch of venison or a savory rabbit stew, may believe it was

very good indeed, for game was plentiful. There were a few

luxuries, too, brought from the old country, for they had not

yet felt the need of hoarding their food supply.

It was a white Christmas, such as we in

Maine know so well. Snow came early that year and covered

everything with a thick, white blanket while the river was

filled with ice. What if the wind did roar through the trees and

whistle down the flues! Their houses were well built and there

was plenty of wood to heap upon the fires. These gay,

light-hearted and venturesome Frenchmen, always ready for

laughter and jest, were quite different from the sober and

serious minded Pilgrims of Plymouth. Fortunately, they could not

foresee the terrible severity of the winter and the sufferings

they must undergo before spring, and they celebrated their

holiday in merry and carefree mood.

But first, they attended solemn services

in the little chapel, just completed. There were probably two

services, one for the Protestants, conducted by their minister,

the other for the Catholics, with a priest in charge. The older

men gathered in the large hall, built for recreation and

meetings, around the blazing fires, and told stories of previous

adventures and recalled happy days in France. The young men went

skating upon the river and rabbit-hunting along the shores.

Later came the feasting and merry

making. A special feature of the entertainment was the reading

of a little paper, called the "Master William," which enlivened

their spirits during the winter. Of course it was written

instead of printed, and there was but one copy, which was passed

around from one to another or read aloud before the company. It

contained the daily events and gossip of the settlement, and we

may be sure the witty Frenchmen worked in some bright jokes at

each other's expense. It is a pity no copies of this first

American newspaper were preserved. However, Champlain makes

mention of it in his journal.

While DeMonts was commissioned the head

of the expedition to form a colony on the North American shores,

Samuel Champlain, historian and navigator, was the real, live

spirit of the party and responsible for much of the Christmas

gaiety. It was he who led the explorations, who gave courage and

ambition to the men and even to the leader, DeMonts, him-self,

and who made the first reliable and fairly accurate maps and

charts of the Maine and Massachusetts coast. No more gallant and

picturesque character is to be found in our early history than

this "true Viking.''

Probably you know Champlain best in

connection with the lake which bears his name, on the western

border of Vermont, and as the founder of Quebec. You may never

have thought of him in connection with the history of your own

State. The general histories of the United States seem to have

neglected that part of his career, but Champlain himself thought

it of sufficient importance to give many pages of his journal

and his "Voyages'' to descriptions of the Maine coast and his

temporary settlement at St. Croix.

|

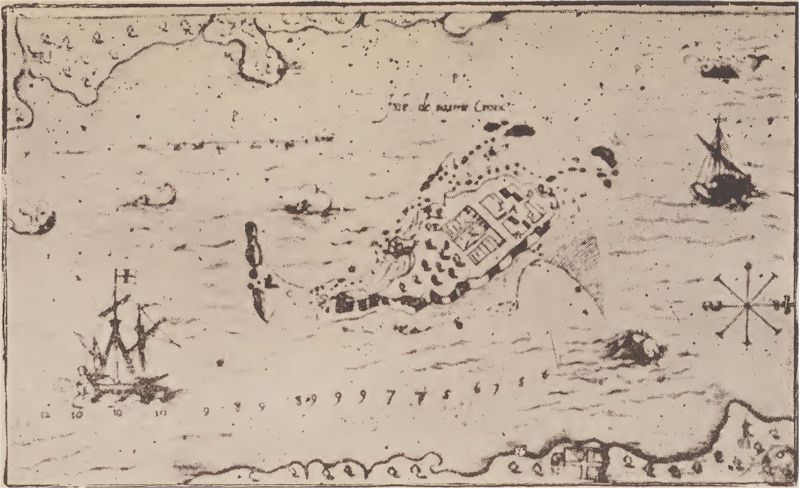

| One of Champlain's Maps,

Showing DeMonts Colony on St. Croix Island |

They are still to be seen, these curious

journals of Champlain, written in French, in stiff, precise

handwriting, something like that you see in very old copybooks,

generously illustrated with colored pictures of the ports,

islands, harbors and rivers he visited, besprinkled with the

beasts, birds and fish that inhabited them, all drawn as your

small brother might draw them and with quite as entire disregard

of the rules of drawing. However, when Champlain drew pictures

of Indians feasting, dancing and scalping their victims, he left

no room for doubts as to what his pictures represented.

Champlain was born in 1567, in the little French town of Brouage,

on the Bay of Biscay. His father was a captain in the royal navy

and one of his uncles was pilot in the king's service. So you

see he was familiar with boats from his childhood. He was

equally familiar with warfare, for all through his boyhood,

civil and religious wars were going on in France, and Brouage

was an important military post. He saw his home town frequently

attacked, captured, restored and re-captured, and soldiers and

the noise of battle were matter-of-course to him. There were

periods of peace, however, and then Samuel attended good schools

and learned to write fluently, to draw maps and think for

himself.

Of course Samuel fought for his king. He was made a

quartermaster, but little is known of his army life. He also

took every opportunity to travel and on one voyage visited the

West Indies and finally explored inland as far as the city of

Mexico. He stopped at Panama and the idea occurred to him that a

ship canal cut thru the Isthmus would be a great institution and

''shorten the voyage to the South Sea more than 1500 leagues."

Such a canal, as you remember, was opened to the world but a

very few years ago, more than two centuries and a half after

Champlain thought of it.

On his first trip to North American

shores, Champlain sailed up the St. Lawrence River as far as

Montreal. Returning with a wonderful narrative of his

adventures, he found King Henry and his viceroy, DeMonts,

planning the founding of a colony in Acadie, on the northern

shores of America.

What more natural, in looking for a

pilot for the expedition, than that they should turn to

Champlain, an experienced and courageous navigator, who was both

soldier and sailor and who combined bravery with prudence and

determination with light-heartedness.

So, in the early spring of 1604,

Champlain sailed with DeMonts in one of his vessels. Pontgrave,

with whom Champlain had made the trip up the St. Lawrence the

year before, followed a few days later, with supplies for the

new colony.

Picture in your mind the quaint little vessel, no larger than

the fishing smack of today, gliding under the frowning crags of

Grand Manan, on a beautiful morning in early summer, and up the

river which marks today the boundary of Maine and New Brunswick.

Crowded on the decks was as curiously assorted a company as ever

set out to found a colony. The best of France were mingled with

the meanest. There were nobles from the court of Henry IV and

thieves from the Paris prisons. There were Catholic priests

rubbing elbows with Huguenot ministers; there were volunteers

from noble families and ruffians flying from justice.

While the company lacked the unity which

made the famous Plymouth colony live, in spite of hardships,

there were competent men as leaders and DeMonts had companions

of his own kind. There were two of his old comrades in service,

Jean Biencourt and the Baron de Poutrincourt; Samuel Champlain,

skilled pilot and royal geographer; Sieur Raleau, DeMonts'

secretary; Messire Aubry, priest; M. Simon, mineralogist, two

surgeons and other men of education and position, who are

mentioned by Champlain in his journal. Later, they were joined

by Lescarbot, a jolly, good-humored fellow, who proved such a

"good sport" that he added much to the cheer of the colony and

he left some of the most entertaining accounts that have been

written of any of the early explorations. He was a natural born

story-teller and entertainer, a poet and familiar with classic

myth and literature, as his writings show. Less matter-of-fact

than Champlain, he had an eye for the humorous and the

picturesque.

They had sailed but a few miles up the

river of the Etechemins, when they came upon a small island,

containing some twelve or fifteen acres, and fenced round with

rocks and shoals. Both Champlain and DeMonts were much taken

with this island.

Anchors went overboard and all hastened

to go on land. That very day a barricade was commenced on a

little inlet and a place made for the cannon, the men working as

fast as they could, considering the mosquitoes, for Champlain

wrote: "the little flies annoyed ns excessively in our work, for

there were several of our men whose faces were so swollen by

their bites that they could scarcely see."

DeMonts named the island St. Croix

because "two leagues higher there were two brooks which came

crosswise to fall within this large branch of the sea."

According to all accounts, the island

presented a very busy scene for the next few weeks. At its

southern extremity, DeMonts planted the heavy guns. Not so many

years ago cannon balls were dug out of the sward here, and, near

the close of the eighteenth century, when the boundary between

the United States and Canada was being settled, the

commissioners traced the foundations of buildings long since

crumbled away, the only remains of the first settlement on the

Maine coast.

First there was the line of palisades to

be established on the north side of the island. Champlain showed

himself to be no less useful on land than on sea. He it was who

drew the plans for the new colony. He located the buildings for

sheltering its members, the workshops, a well and two great

garden plats. When DeMonts had located the storehouse and seen

it started, he gave his attention to a residence for himself,

which, the chronicles say, was built by good workmen.

The end of August saw the work so well

advanced that DeMonts sent his friend, Poutrincourt, back to

France, he agreeing to return in the spring with reinforcements

and supplies. DeMonts kept one ship with Capt. Timothee to

command it, and seventy-nine men. This was three months before

the Christmas day of which you have just read.

Emmie Bailey Whitney

|

![]()

![]()