Four Forts of Pemaquid

Forts, Pirates and Indians!! Are there

any three words which would grip the average boy harder and hold

before him better the Great Adventure? Where were these four

wonderful forts, is the first question. If you will follow the

jagged coastline of Maine from Portland to beyond where the

Damariscotta River flows into the ocean, you will find a long

point of land marked Pemaquid, at the south end of which stands

a noted lighthouse. This point is about three miles long and

extends to the mouth of the Pemaquid River where that meets

Johns Bay and forms the inner harbor and nearly surrounds a

small peninsula of about eighteen acres upon which the four

forts have been erected. Here, too, were found the buried paved

streets, of which no one knows the history, and hundreds of

walled cellars, which have been mostly filled up. That little

spot holds more history to the square foot than any town in

Maine. This point forms the east side of the great bay, which

with its island in the center, was named by the celebrated Capt.

John Smith of Pocahontas fame when he was sent to this country

by the King of England in 1614, six years before the arrival of

the Pilgrims at Plymouth. A few men had come there and built

rough cabins for a bare shelter while they traded in fish and

furs, bartered from the Indians in exchange for beads and bits

of finery. Later other men came really to settle there; to build

small houses; to farm the land as well as to engage in fishing.

The Indians, at first friendly, had been

brought into the troubles between England and France, who in

those days were always fighting each other. For the most part

the tribes of Maine sided with France in the quarrel. The

English had cheated them a bit more and had been much more cruel

to them and now were trying to drive them away from the coast to

the inland forests. The Indians, angered by these acts, often

attacked small groups of settlers. Thus the pioneers at Pemaquid

found they must have some protection against wandering bands of

Indians, so they built a house called a block house. It was

round without windows, but with loop-holes through which to put

the muzzle of their muskets to fire on the foe. It was large

enough to hold all the men, women and children of the

settlement, though of course they were crowded. Around it was a

high fence called a stockade which enclosed a yard where there

was a well in case of siege.

Ten years after this fort was built on

what is now called Fort Rock, while Captain Shurt was in

command, there was an attack. Remember it was built to keep away

the Indians and who do you suppose made that attack! Did you

ever hear of Dixy Bull? All along our Maine coast were little

schooners gathering up the fish caught and cured by the

fishermen and the furs sold by the Indians and taking them

either to Plymouth Colony or to the Mother Country (England).

Every little while a pirate ship flaunting its black flag would

sail along the shores, making an attack sometimes on a fishing

boat and sometimes on the poor settlers. One of the boldest of

these pirates was the famous Dixy Bull and in 1632 he swooped

down on Shurt's fort, plundered it and plundered all the farms

near. He was the leader of the whole pirate crew and lost but

one man in this attack.

|

| Old Fort Frederic, Pemaquid |

|

| Fort at Pemaquid as it Looks

Today |

When Gov. Winthrop at Boston learned of

Bull's wicked deeds, he sent four small vessels with forty men

aboard and others joined in the pursuit, determined to drive all

pirates from the Maine coast. However, this time Dixy was quick

enough to escape. Some years after he was captured and taken to

England where he was severely punished.

The second fort at Pemaquid was called Fort Charles. It was

built in 1677 under the direction of Sir Edmond Andros, then

colonial governor of New York. Like the first fort, it was built

of wood, two stories high, with a stockade or high fence around

it. It also was built to keep the Indians away.

On Penobscot Bay at a place called

Pentagoet (Castine) lived a Frenchman, Baron Castin, who owned a

trading house there with a fort and Catholic Mission. In 1689

France and England were not in open war but were constantly

making raids against each other. The year before, Andros had

pillaged Castings house and now the Baron plotted revenge on

Andros' fort at Pemaquid. He easily secured the help of the

Indians because he had married the pretty young daughter of the

celebrated chief, Madockawando, which made him a member of their

tribe.

Castin sent three canoes ahead to see

that the way was clear and the plan was for them to wait two

leagues from the fort, probably at what is now Round Pond. After

landing, they marched, with great caution, toward the

settlement. On their way, they took three prisoners, from whom

they learned that about 100 men were in the fort and village.

One of the three captives was named Starkey and, in exchange for

his own liberty, he told the Indians that at that particular

time only a few men were in the fort, as Mr. Giles, with a party

of fourteen men, had gone up to his farm to work, three miles up

the Pemaquid River. The Indians, thereupon, divided their little

army. Part, going up to the Falls, killed Giles; the rest

started for the fort and took their position between the fort

and the village, so as to cut off the men as they came in from

the fields where they were at work.

The firing between the Fort and the

Indians ceased only with darkness, when the besiegers summoned

the commander to surrender the fort and received as a reply from

someone within that "he was greatly fatigued and must have some

sleep."

At dawn, the firing on both sides was

renewed; but soon the firing from the fort ceased and Lieut.

James Weems, the commander, agreed to surrender. Terms were

made, the commander soon came out, at the head of 14 men, all

that remained of the garrison. With them came some women and

children with packs on their backs.

The terms of surrender included the men

of the garrison and the few people of the village who had been

so fortunate as to get into the fort, with the three English

captives who had previously escaped from the Indians. They were

allowed to take what-ever they could carry in their hands and to

depart before, from Capt. Padeshall, who was killed as he was

landing from his boat. All the men and women and children of the

place who had not been in the fort and had not been killed in

the fight, were compelled to leave with the Indians for the

Penobscot River. They made the passage, some in birch-bark

canoes and the rest in two captured sloops. The whole number of

captives thus taken was about 50; but how many were killed no

one knows exactly. The number of soldiers killed was about 16.

Weems himself was badly burned in the face by an accidental

explosion of gunpowder.

One of the captives was Grace Higiman

and the following story of her experiences in captivity will

interest you.

"On the second day of August, 1689, the day Pemaquid was

assaulted and taken by the Indians, I was there taken prisoner

and carried away by them, one Eken by name, a Canadian Indian,

pretending to have a right to me, and to be my master. The

Indians carried away myself and other captives (about 50 in

number) unto the Fort of Penobscot. I continued there for about

three years, removing from place to place as the Indians

occasionally went, and was very hardly treated by them both in

respects of provisions and clothing, having nothing but a torn

blanket to cover me during the winter seasons, and oftentimes

cruelly beaten. After I had been with the Indians three years,

they carried me to Quebeck and sold me for forty crowns unto the

French there who treated me well, gave me my liberty, and I had

the King's allowance of provisions, as also a room provided for

me, and liberty to work for myself. I continued there for two

years and a half."

In 1692 after Sir William Phips, the

first Colonial Governor of Massachusetts, of which Maine was

then a part, had captured Port Royal, he came to Pemaquid to

arrange to have a strong fort built which should maintain the

rights of England to that eastern territory and prevent attack

of the Indians on the western settlements. He knew this part of

Maine well as his boyhood had been spent here. The new fort was

built of stone, about 700 feet square. It had fourteen mounted

guns, about half of them 18 pounders; the sea wall was 22 feet

high with a round tower somewhat taller toward the west, built

around the great rock at the west corner which the Indians had

used to capture Fort Charles; two hundred cart-loads of stone

were put into the building; sixty men were left for its defense.

This fort was a great annoyance to the Indians as it was on

their direct line of travel on the sea coast.

Another trouble was arising between two

French frigates and two British ships sent out to capture them.

D 'Iberville, commander of the French, allied himself with Baron

Castin who brought with him two hundred Penobscot Indians. D

'Iberville had one hundred more aboard his ships, while Villieu,

a French officer with twenty-five French soldiers, joined them.

The three ships made sail for Pemaquid, the Indians covering the

distance in their canoes.

The next day, August 14th, they ordered

the fort to surrender. Its captain, Pasco Chubb, a born fighter,

sent back word. "If the sea was covered with French vessels and

the land with Indians, I would not surrender."

During the night the French came ashore

with guns and the next day from a high bluff began throwing

bombshells inside the fort. The soldiers and the people gathered

within the fort probably had the surprise of their lives. Here,

then, were bomb-shells, brought into use, probably, for the

first time in the history of warfare in this country. It is

certain the English had no bomb-proof covers for the protection

of those within the fort. Consternation and despair came with

this new shrieking element of destruction; for it seemed that

they were gathered like a helpless flock of sheep, to perish

together.

Then Castin sent a letter into the fort,

which informed them that if they would surrender, they should be

transported to a place of safety, and receive protection from

the savages; but if they were taken by assault, they would have

to deal with the Indians and must expect no quarter.

Terms of surrender were agreed upon by

the officers of the fort. All marched out and were taken to one

of the islands nearby for protection from the Indians while

Villieu, with sixty French soldiers, took possession of the

fort. They found an Indian confined with irons in the fort, who

had been a prisoner since the previous February. He was in

pitiable condition.

The fourth fort was named Fort Frederic,

in honor of the young Prince of Wales. It was built in the

spring of 1729, by David Dunbar, who came to Pemaquid from

England for that express purpose, bringing his family with him.

He had a royal commission as governor, from the British

government, authorizing him to rebuild the fort, as the

Massachusetts government had failed to do it.

Many bloody tales of warfare might be

related, concerning Fort Frederic, stirring tales of adventures

and records of trials endured by these hardy border settlers.

One of the tales handed down, relates how the Indians, on one of

their unexpected visits, found a mother with her two daughters,

picking berries some distance from the fort. All fled for

protection toward the fort and the mother and the older girl

reached it, barely escaping with their lives. The younger girl,

not more than eleven years old, was seized and scalped. And now

comes the remarkable part of the story. The savages threw the

little girl, whom they supposed to be dying, on a pile of rocks,

where the sun shone directly down on her unprotected head. The

kindly, healing rays of the sun quickly dried the blood and

stopped any further flow and her life was saved. And so she

lived to grow up, one of the very few who ever survived the

scalping knife.

When the French and Indian war closed

with the fall of Quebec, in 1759, the usefulness of the fort was

ended. After a few years of peace, in 1762, the great cannon

were carried away to Boston.

When the Revolution began, April 19,

1775, Pemaquid people became alarmed and, in town meeting, voted

to tear down the old fort, so that the British could not use it

against them.

Today, near Pemaquid Beach, you may see

the ruins of the old fort, marked by the old Fort Rock of

Pemaquid, with the date of 1607 upon it. This is the date of the

landing of the Popham colonists, the first English people at

that place, August 8 and 10, 1607, thirteen years before the

landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock.

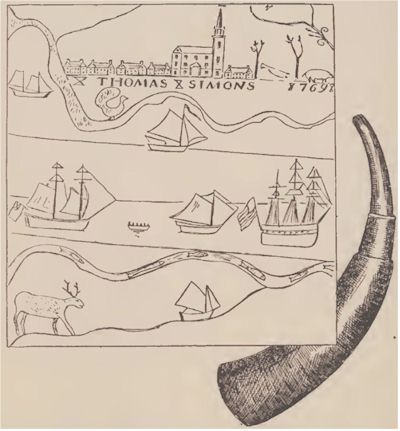

|

| Indian Horn |

Horn presented by the Indians to the

commander of Fort Frederic. The accompanying sketch was carved

on the horn, and is supposed to picture historic scenes at

Pemaquid. The tall spired church as an emblem of English

worship, indicated a religious community; the water sketching of

the little river Pemaquid with varied navigation afloat,

indicated the commercial aptitude and business of the Fort

Frederic Settlement in the early period of English life there;

the turkey cock, fish and deer are indications of the resources

in game and the industries in furs and fisheries - fishery

predominating.

Fort Rock is now surrounded by the old

castle, restored on the original foundations and with most of

the original stone of which it was first built by Sir William

Phips in 1692. This foundation was discovered in 1893, in good

condition, after being buried and forgotten since the American

Revolution.

Here, also, is the old Fort House on its

beautiful peninsula, with its "field of Graves," the site of the

ancient capital of Pemaquid, with its paved streets, which had

been buried for centuries and only discovered by accident, to

remind us of a people long ago forgotten.

Note. - The material in this story is

from Cartland's "Twenty Years at Pemaquid."

|

![]()

![]()