The Hero of Little Round Top

Among her heroes, Maine will always have

a place for Gen. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, 'The Hero of

Little Round Top."

Little Round Top was a hill on the field

of Gettysburg, Pa., where a decisive battle of the Civil War was

fought and where the gallant troops of the North repulsed the

attacks of the Southern armies in a fierce, hand-to-hand

conflict that was marked by heroism and devotion, on both sides.

Here, on a hot day in July, two days

before the anniversary of American Independence of that year,

the troops of the 20th Maine Infantry, forming the extreme left

of the National defense, sustained the assaults of Gen.

Longstreet on the extreme right of the Confederate armies, and,

turning again on them, drove them from the field, saved the

heights and took many Confederate prisoners, leaving the

hill-top strewn with dead and wounded.

The leader of the Northern troops in

this heroic stand for the Union on Little Round Top was General

Chamberlain, a soldier, a scholar, a statesman, afterward a

Governor of Maine and President of Bowdoin College and ever a

gentleman of winsome and gentle manner, great in peace as he was

in war.

When the war broke out in 1861, Gen.

Chamberlain was only 28 years of age, a Professor at Bowdoin,

from which he had been graduated six years before. He was born

in Brewer, Maine, on a farm and, by his own scholarly

attainments, his fine bearing and his nobility of character, had

attained supremacy in many branches of work. When the war broke

out he immediately offered himself to his country. After he had

become famous, a lady once asked him how he happened to have

been in the Civil War. ''Madam," said he, "I didn't happen." He

did not "happen'' to be in the war; he went, as a soldier should

go, eager to be of service to human freedom. He was given a

lieutenant's commission; became Colonel; he saved Little Round

Top, the most important position of the great battle of

Gettysburg against a foe that outnumbered his troops three to

one, and before the end of the Civil War, he was a Major-General

of the Union armies.

He was a very handsome man, erect, tall, with a flashing eye, a

strong, musical voice. Apparently regardless of danger he was

willing to lead his men into any place where duty called. In the

bloody battle of Petersburg, he was leading his troops to

assault when a bullet passed through his body. He believed the

wound to be mortal. He felt his life-blood ebbing away with his

strength; yet he stood, leaning upon his sword, ordering the

advance. Thus he stood until the last man of his command had

passed him; and then, when no soldier of his should see him

fall, he fell to earth and was carried from the field, as though

dead. Six times was he wounded during the war and for all of his

life, afterward, he suffered continually. At Little Round Top,

he was fearfully wounded in the charge that passed up the hill

in which the Maine boys drove the Southern soldiers from the

hill, capturing over 800 Confederate prisoners in the assault.

As he lapsed into unconsciousness, he grasped firm hold of a

little bush beside which he had sunk. Years afterward, when

Gettysburg had become a memory, he still retained the

impressions of that moment and he said, "I felt that if I let go

of that little shrub, I should die. I thought that with release

of that, my soul would leave my body." And so, in the intervals

of pain and unconsciousness, he kept fast hold until he was

carried from the battlefield to be restored later to health and

strength.

From Gettysburg to Appomattox, Gen.

Chamberlain, in spite of all his wounds, was able to follow the

course of the victorious armies of the North. Appomattox was the

last great battle-field of the war. It was here that the Army of

General Robert E. Lee laid down its arms, stacked its

battle-flags and with generous terms of surrender from General

U. S. Grant, dispersed sadly to its homes. When the historic

moment for the surrender came and when it became the duty of

General Grant to receive Gen. Lee's sword in token of complete

surrender, it was Gen. Chamberlain who was deputed to receive

the sword of the great Southern general. Seated on his horse,

his uniform soiled by smoke and dust, Gen. Chamberlain watched

the ragged Confederate troops file by. As one Confederate color

bearer delivered up the tattered flag of his regiment, he burst

into tears, saying, ''Boys! You have all seen this old flag

before. I had rather give my own life than give up that flag."

The sentiment touched Gen. Chamberlain and he made the remark

that endeared him to the South and was repeated thousands of

times: "Brave fellow! Your spirit is that of the true soldier in

any army on any field. I only regret that I have not the

authority to bid you take that flag, carry it home, and preserve

it as a precious heirloom of a soldier who did his full duty."

General Chamberlain came home to Maine

after the war, one of the most honored and beloved of the

soldiers of that great struggle. His college made him its

President. His State made him four times a governor. He brought

back to Maine his wounds, his suffering and his wonderful spirit

of devotion to humanity. His hair was as white as snow. His face

was set in lines that indicated the stormy background of his

life. It was a suggestive picture to see him about the town of

Brunswick, driving his old war-horse, Charlie, one of six horses

that he rode in the service, five others having been shot under

him. Twice his horse saved the life of his master. Once a bullet

went into the horse's neck that otherwise would have struck his

rider and once the horse galloped from the field with his

unconscious master upon his back. Charlie died in Brunswick and

was buried near Gen. Chamberlain's summer home by the sea.

It has been said that the greatest

soldiers are often the tenderest and most considerate of men.

This has been true in many cases but not always. It was true in

the case of Gen. Chamberlain. He had difficulty in saying ''no"

to any person seeking his favor. He saw the high and noble

heroism of his foes, even though he felt the injustice of their

cause. He was a firm and lasting friend of General Lee of the

Southern Armies.

He was once cruising among the Casco Bay

Islands, when his yacht was visited by a party of picnickers.

Gen. Chamberlain joined them on the shore around their campfire

and here he told stories of the war. It was in the era when ill

feeling yet ran high between North and South and another member

of the party followed Gen. Chamberlain by severe arraignment of

the South.

In the party was a young lady from

Virginia whose feelings were deeply hurt by the tirade. One

person alone noticed; this was Gen. Chamberlain. With his

customary kindness and thoughtfulness, he began telling stories

of the bravery and generosity of his foe and so won back the

smiles to the young girl's face and left her full of admiration

for the generous and gallant general of the North.

These qualities of human sympathy made

him a magnetic orator and a wonderful writer. His oration on

Maine, delivered by him at the Centennial Exposition in

Philadelphia in 1876, stands out as the finest historical

address ever delivered on any subject connected with Maine and

with perhaps no equal among the addresses of similar scope, in

the history of our country. He wrote the most beautiful English

and he spoke it as well. He was author of many books especially

connected with historical matters touching his native State and

the Civil War. Later in life, he recounted in a series of

magazine articles, subsequently put into a book, all of his war

time memories, and they are as interesting and as freshly

vigorous and picturesque as though written by a young man,

instead of by a man long past the allotted term of life.

Thousands of boys loved and admired Gen,

Chamberlain. He met them all over the world in his travels, boys

whom he had helped through college. A friend of Gen. Chamberlain

was once standing in front of the Parthenon, the ruin of the

renowned Greek temple at Athens, when the photographer, an

Armenian, hearing the word "Bowdoin College" asked for Gen.

Chamberlain. "I adore Gen. Chamberlain," said he. ''I was a

persecuted Armenian, He loaned me the money to give me my

education." This young man was a photographer of renown and a

photograph of the statue of Hermes, which he sent to Gen.

Chamberlain, hung in the Brunswick home of the General up to the

time of his death.

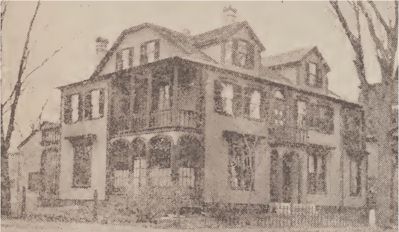

The death of Gen. Chamberlain occurred

at Brunswick in 1914, at the age of 86 years. The house where he

lived and died in Brunswick was the home of Longfellow, when he

lived and taught at Bowdoin. Gen. Chamberlain lies buried not

far from his Brunswick home. His funeral was a great military

and civic honor. He died in the love and veneration of his

country and of his State, having proved by his life and his

death the virtues as well as the victories of a Christian

soldier and a true and cultured gentleman.

|

| Home of General Chamberlain in

Brunswick |

|

![]()

![]()