Along the Maine Coast with Champlain

It was right away after Poutrincourt's

return to France that Champlain started ont on an enterprise of

his own. He had long cherished an ambition to search ont the

fabled city of Norumbega, which, he reckoned, could not be many

leagues from St. Croix, and find out for himself how much truth

there was in the glowing reports of David Ingram.

I may as well tell you now that in this

Champlain was disappointed. He confessed that there are none of

the marvels which some persons have described, "although he

visited the precise location of Pentagoet. He recorded with some

disgust, "I will say that since our entry where we were, which

is about twenty-four leagues, we saw not a single town nor

village nor the appearance of one having been there, but only

one or two huts of the savages where there was nobody. "

|

| Samuel Champlain |

Marc Lescarbot, also, wrote in his usual

blithe style: "If this beautiful town ever existed in Nature, I

would like to know who pulled it down, for there is nothing but

huts here made of pickets and covered with the bark of trees or

with skins."

It was the second or third day of

September that Champlain set out with, some historians say,

twelve, and some say seventeen men of the colony and two Indians

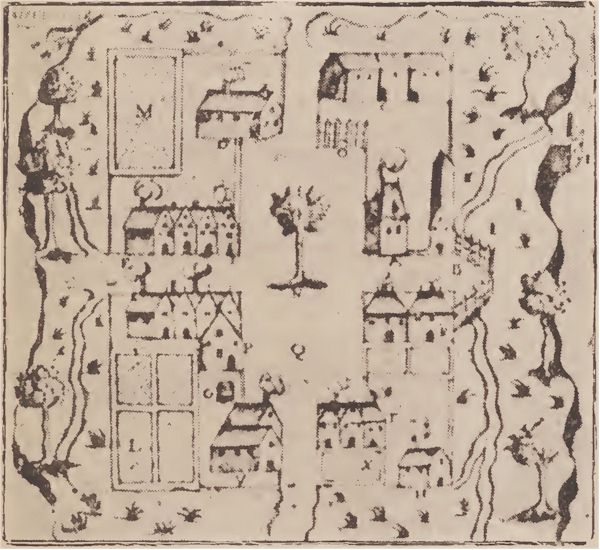

as guides, in his "patache." This big, open boat, fitted with a

lateen sail and oars, is pictured in Champlain's drawing of the

St. Croix settlement.

The second day out they passed an island

some four or five leagues long. "The island is high and notched

in places so that from the sea it gives the appearance of a

range of seven or eight mountains. The summits are all bare and

rocky. The slopes are covered with pines, firs and birches. I

named it Les Isles des Monts Deserts," Champlain wrote. And this

is the first account of the naming of Mount Desert Island, on

which is Bar Harbor, the now famous summer resort.

"On the third day the savages came alongside and talked with our

savages. I ordered biscuit, tobacco and other trifles to be

given to them. We made an alliance with them and they agreed to

guide us to their river of Peimtgouet, so called of them, where

they told us was their captain, named Bessabez, chief of that

place."

The river was the Penobscot we know so

well, and the stopping place, where the council with the Indians

was held, was the present site of Bangor.

Champlain, continuing on his voyage of

discovery, sailed down the river, passed out by Owl's Head and

westward to the Kennebec, which he called Qinnibequy. He arrived

at St. Croix, having been away just a month. They did not reach

the settlement any too soon. Snow fell that year as early as the

6th of October, and by Christmas, as you have already seen,

winter had set in with unusual severity.

|

| Champlain's Sketch of St. Croix

Settlement |

''Hoary snow-father being come," as the

poetical Lescarbot expresses it, ''they were forced to keep much

within the doors of their dwellings."

When the north winds swept down the

river and whistled through the rows of cedars, the sole

protection of the island against the wintry blasts, the poor

Frenchmen did not venture out-doors, but shivered around their

fires and Champlain remarked that "the air that came in through

the cracks was colder than that outside.'' There were no cellars

under the houses so vegetables and every liquid froze. Champlain

mentions dealing out the frozen cider by the pound.

Their fare, too, was scanty. They ground their grain, as they

needed it, in a hand mill, a tiresome process. They had salt

meat only. This soon began to affect the health of the men.

Scurvy broke out. The colony physicians had all they could do,

but it is not likely that they had the proper medicines, and out

of the seventy-nine men, thirty-five died before spring and

others were bloated and disfigured.

It was not until the fifteenth of June,

as the guard went his rounds a little before midnight that

Pont-Grave, so long and anxiously awaited, came in a shallop,

with the news that his ship was but six leagues away, lying

safely at anchor. There was great rejoicing at the settlement

and little sleep for anyone for the rest of the night.

Two days after the arrival of

Pont-Grave's ship, Champlain set out on a second voyage down the

coast. With him were M. Simon and several other gentlemen and

twenty sailors to man the boat, also the Indian, Panounais and

his squaw, as guides.

It was an eventful voyage and Champlain

writes fully and entertainingly about it.

Near Prout's Neck more than eighty of the savages ran down to

the shore to meet the strangers, "dancing and yelping to show

their joy.''

The Indians believed there was some

magic about Champlain and his companions, who, they said, "must

have dropped from the clouds." When Champlain was invited to a

feast of the Indians, he was told by his Indian guide that he

must not refuse. So he took his place among them, "squatted on

the skins spread for the guests of honor, around large kettles

of fish, bear's meat, pease and wild plums, mixed with the

raisins and biscuits they had procured in trade with the white

men, the whole well boiled together and well stirred with a

canoe paddle."

When Champlain showed great hesitancy in

eating the portion set before him, we are informed in the

chronicles that his hosts tried to tempt his appetite with a

large lump of bear's fat, a supreme luxury in their estimation,

whereupon he took a hasty leave, stopping only to exclaim, "Ho,

ho, ho," which his guide informed him was the proper way of

saying "please excuse me," to an Indian host.

On July twelfth, Champlain and his party

left the Front's Neck vicinity and steered their course ''like

some adventurous party of pleasure," we are told, by the beaches

of York and Wells, Portsmouth Harbor, Isles of Shoals, Rye Beach

and Hampton Beach, and into Massachusetts Bay, which they

explored at their leisure. Champlain was the most troubled by

the mosquitoes, which ''pestered him beyond endurance," to use

his own words.

DeMonts found no place on the

Massachusetts coast more suitable for his colony than St. Croix

and by July 29 they were back at the mouth of the Kennebec,

where they had an interview with the Indian chieftain, who gave

them news of another European ship on the coast. From their

description it must have been the Archangel, commanded by George

Weymouth, who was navigating the New England coast at that time.

It is the only reference made to Weymouth in any of Champlain's

writings.

Provisions were getting low, so they

steered once more for St. Croix. Aside from the killing of the

sailor by the Indians, but one other tragedy marked the year of

1605. It was the killing, by the Penobscot Indians, of their

faithful guide, Panounais. The body of the dead Indian was

brought from Norumbega to his friends in St. Croix, where an

imposing funeral was held. You may like to read Champlain's

description of the savage ceremony. He writes:

"As soon as the body was brought on

shore, his relatives and friends began to shout by his side,

having painted their faces black, which is their mode of

mourning. After lamenting much, they took a quantity of tobacco

and two or three other things belonging to the deceased and

burned them some thousand paces from our settlement. Their cries

continued until they returned to their cabin. The next day they

took the body of the deceased and wrapped it in a red covering,

which Mambretou, chief of the place, urgently implored me to

give, since it was handsome and large. He gave it to the

relatives of the deceased, who thanked me very much for it.

"And thus, wrapping up the body, they

decorated it with several kinds of malachiats; that is, strings

of beads and bracelets of divers colors. They painted the face

and put on the head many feathers and other things, the finest

they had, then they placed the body on its knees, between two

sticks, with another under the arms to sustain it. Around the

body were the mother, wife and other of the relatives of the

deceased, both women and girls, howling like wolves.

"While the women and girls were

shrieking, the savage named Mambretou made a speech to his

companions on the death of the deceased, urging all to take

vengeance for the wickedness and treachery committed by the

subjects of the Bessabez, and to make war on them as speedily as

possible. After this the body was carried to another cabin and

after smoking tobacco together, they wrapped it in an elk skin

likewise and binding it very securely, they kept it for a larger

gathering of savages, so a larger number of presents would be

given to the widow and children."

Soon after this, DeMonts and Champlain

moved the whole settlement to Port Royal. DeMonts soon sailed

for France. The indomitable Champlain volunteered to brave

another winter in the wilds and we are glad to read in his

journal that "We spent the winter very pleasantly."

And now that you have followed

Champlain's adventures along the Maine coast, you may want to

trace them further, among the Indians of Vermont, New York and

the Great Lakes region, and to learn how he became the father of

Canada; how his blithe courage planted the fleur-de-lis on the

rock of Quebec. There, on Christmas day of 1635, just thirty-one

years after his Christmas celebration in Maine, he died,

striving to the last for the welfare of his colony, "for the

glory of France and the church."

As for St. Croix, which he first helped

to settle, it was never after deserted for long at a time. It

remained the most southern foothold of the French until the

cession of Canada to the English in 1763.

Emmie Bailey Whitney.

|

![]()

![]()