With Pepperrell at Louisburg

What American boy or girl whose

grandfather served in the Civil War or whose father was a

soldier in the war with Spain, has not climbed upon his knee and

begged him to tell the story of his wonderful adventures in camp

or on battlefield? And if no relative was a veteran, how eagerly

have the children listened to stories told by Grand Army men at

annual camp-fires on Memorial Day or at Fourth of July

celebrations!

It was just the same with the O'Brien

boys whose father, Morris O'Brien, fought with the colonial

militia that captured the fortress of Louisburg in 1745, then

the strongest fortification in America.

There were six boys in the O'Brien

fami1y, Jeremiah, called Jerry, being the oldest. Then came

Gideon, William, Joseph, John and Dennis. These boys had three

sisters, Martha, Joanna and Mary.

|

| Sir William Pepperrell |

From the time Jerry was a sturdy lad and

Dennis a mere toddler, these boys were never happier than when,

gathered about the big fireplace in their home in Scarboro,

their father related the story of General Pepperrell and the

siege of Louisburg. Before he could begin the story of the great

expedition, the boys always insisted that their father tell

about his voyage across the sea in one of Pepperrell 's ships

and his landing at Kittery where the first thing he saw was the

General's fine mansion as it stood on the hillside facing the

sea.

"You must know, my lads, that although I

was bound out to a respectable tailor of Cork, my old home in

Ireland, and had well learned his good trade, I was not

satisfied to pass all my days cooped in a shop stitching away

with thread and needle and pressing seams with an iron goose. I

yearned to be out in the world, where brave deeds were being

done and where a young man might win a fortune, such as was

never made in a tailor's shop.

"One day" an American sea captain came

to our shop and ordered a suit of clothes to be made within two

weeks, when his ship would be ready for the homeward voyage.

That was like the Americans, I thought, always wanting things in

a hurry. But the master took the order, and gave the work to me,

which, by dint of hard labor, I was able to finish at the

appointed time.

"During the two weeks the captain was

much at our shop, for he was most particular as to the set of

his garments; and while I measured, fitted and stitched, he,

being a genial man, talked much of his life on the sea, of his

ship and her owner, William Pepperrell of Kittery in the

Massachusetts Colony.

"When my work was finished, the captain

had a suit of which to be proud, and so he seemed; for when he

paid the master he slipped a half crown into my hand, saying

that America was just the place for a young man who had so well

learned his trade.

"From that day I determined to go to

America, and the summer following, being twenty-five years old,

I took passage with the same captain in another of the

Pepperrell ships making her maiden voyage.

"I had many talks with the captain

before we reached this side of the ocean and came to know much

more concerning William Pepperrell, his ships and warehouses,

his great estate including several towns and hundreds of acres

of virgin forest between the two rivers, Saco and Piscataqua,

whence came the timber of the vessels built in his own

ship-yards at Kittery. I learned of the splendid mansion,

Pepperrell's home, with the carved furniture and rich hangings,

from whose windows the owner might see his ships discharging

valuable cargoes from foreign lands and still other ships ready

to launch from the nearby yards.

"When I reached America, I soon found

that all the captain told was true. William Pepperrell was not

only the richest man in the colony but also one of the most

respected and beloved because of his noble character, kind and

genial manner toward all, his devotion to the public welfare and

the wisdom and faithfulness with which he performed every duty.

The generous hospitality of his beautiful home was dispensed

alike to neighbors and to guests of high degree.

"When a young man he had been appointed to responsible civil and

military offices and now was president of the Governor's Council

and Lieutenant Colonel of the York County regiment of militia.

"Often did I see the Colonel walking

about the streets of Kittery dressed in a rich suit of scarlet

and gold, with lace frills at wrist and neck and gold buckles at

the knee. More often was he to be seen riding in his great coach

with gay outriders and attendants.

|

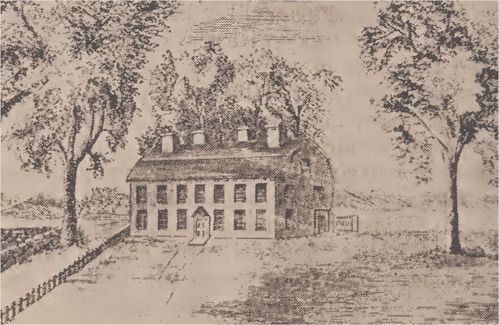

Pepperrell Mansion, Kittery

As it looked in the days of Sir William.

It still stands, but has been remodeled |

"One Sabbath, soon after my arrival, I

went with others of the village to the Pepperrell mansion to

listen to the famous Parson Whitefield, a great friend of the

Pepperrell's and a frequent visitor at their home. The Colonel

welcomed each guest on entering the great hall, and when he

knew^ I was a stranger but lately come to Kittery bade me a

friendly welcome and wished me well. From that moment I would

have served him gladly, even at risk of my life.

"However, I did not remain long in

Kittery, there being no need for another tailor. Upon looking

about, I came to Scarboro and here at Dunstans' Corner I have

had my shop all these years, busy years and happy too, for soon

I met your mother and now you children are all here. Only once

have I parted from home and dear ones and that was at the time

when I went with other men of Scarboro to help capture the great

French fortress at Louisburg."

Chapter II.

"Tell us about Louisburg," the children

pleaded.

"That is a long story," said Morris

'Brien.

"The news that France and England had

declared war reached Louisburg several wrecks before it was

known in Boston and the French Governor soon sent out a party of

soldiers and Indians who captured the village of Canso in

Acadia, burning the dwellings and taking eighty prisoners back

to Louisburg,'' Morris O'Brien continued.

"When this became known in New England,

the people, who remembered the last war with the French, were

filled with terror at what might befall their homes and families

at the hands of these French war parties.

"Our Colonel Pepperrell sent word to all

his captains to be prepared for attacks and added, "I hope that

he who gave us breath will also give us courage to behave

ourselves like true-born Englishmen.' This message encouraged

the people, but all felt that so long as Louisburg was a French

stronghold there was no promise of safety.

"Moreover,' O'Brien continued,

"merchants like Pepperrell, who had many vessels engaged in the

fisheries and in trade with Europe and the West Indies, knew

they would meet great losses; for the French warships would sail

out from that safe harbor and capture their vessels, crews and

rich cargoes.

"For these reasons, the people of the

Colonies longed to see Louisburg captured and were willing to

help reduce it. Our Governor Shirley and others were planning

how this might best be accomplished when the Canso prisoners,

who had been kept at Louisburg for several months, were sent to

Boston, as the French had promised them.

"These men were eagerly questioned by

the officials who wished to know more about the place and the

strength of the fortifications. They replied that although the

fort was strong and well fortified with powerful guns, the

garrison was mutinous, the supplies of food were low and no more

could be obtained until the ships came from France in the

spring.

"So it was plainly seen that even a small army might capture

Louisburg, if it attacked just as the ice was breaking up the

following spring, before help arrived from France. And this was

the plan decided upon by the Colonial authorities.

"When Governor Shirley called for volunteers and we heard that

our beloved Colonel Pepperrell had been appointed to lead the

expedition, there was excitement and enthusiasm everywhere, for

we believed that, with Pepperrell as commander, we should be

successful.

"You may be sure I was among the first

of the Scarboro men to enlist and was in the first company of

the General's own regiment.

"It was early in February when enlisting

began and so rapidly were the regiments recruited and supplies

obtained that within two months the forces were on transports in

Boston Harbor ready to sail for Louisburg.

"Meanwhile a fleet of thirteen armed

vessels had been collected and, with Capt. Edward Tyng of

Falmouth as commodore, sailed in advance of the trans-ports to

capture any French vessels that might try to get into Louisburg

with supplies. The expedition was also joined by a small

squadron of the Royal Navy, which had wintered in the West

Indies, commanded by Sir Peter Warren. This proved of great

importance during the siege, for with the colonial fleet a

strict blockade of Louisburg Harbor was maintained and several

French ships captured.

"It had been planned to surprise the

French if possible, but when we reached Canso it was found that

an immediate attack was impossible, for the waters around Cape

Breton Island were still ice-bound. So the troops were landed at

Canso. Here we passed three weeks impatiently waiting for the

ice to clear. We used this time to good advantage in building a

battery and block house, preparing necessary supplies and in

daily drill.

"On April twenty-sixth word was brought

by one of the cruisers that the ice had left Gabarus Bay and

three days later we sailed for Cape Breton Island.

"Of course it was impossible to surprise

the French, for they had seen our fleet and sent a force of

soldiers from the fort to prevent our landing. General

Pepperrell easily deceived them as to the place by sending out

several boats towards Flat Point, but, when near to the shore,

they suddenly turned and came back toward the transports. Other

boats then joined them and they pulled at top speed for a small

cove two miles above the point, and reached it sometime before

the French could march around by land. "When they did arrive,

enough of our men were ashore easily to drive the French back to

Louisburg. Thus we were unopposed, and during the day landed two

thousand men.

"General Pepperrell lost no time in

finding out all that could be learned regarding the region

around Louisburg. That first afternoon he sent Colonel Vaughan,

one of his most fearless and resolute officers, with four

hundred soldiers to reconnoiter.

"At night Vaughan sent all except

thirteen of his men back to camp with his report, but he and the

thirteen passed the night in the woods.

''In the morning occurred the most

fortunate event of the siege. When Vaughan and his little

company of men, on their return, came opposite the Royal

Battery, nothing was to be seen of the garrison. One of his men,

a Cape Cod Indian, was sent forward to investigate and found

that the French had abandoned the Battery during the night after

spiking the guns.

''Vaughan and his men took possession of

the Royal Battery which the French had abandoned, and William

Tufts, a lad of eighteen, climbed the flag-pole and fastened to

its top his scarlet coat as a substitute for the British flag.

"This Royal Battery was indeed a prize

for it not only commanded the harbor, and if held by the French

could easily have kept off our blockading ships, but it

contained thirty-five cannon of which we were in sore need.

These had been hastily spiked, but Major Pomroy, a gunsmith by

trade, soon had them drilled open and before night they were

ready to use against the fortress.

"Soon a tremendous difficulty presented

itself. General Pepperrell had ordered a battery of our guns,

which had been landed from the transports, placed on Green Hill,

the first in the range north of the fortress. This hill was two

miles from our camp and the intervening land was a low, wet

swamp. When we tried to drag the first gun across this swamp,

the wheels of the carriage at once sank to the hubs in moss and

mud, and, before long, carriage and gun had disappeared. What

could be done? Our difficulty was solved by Colonel Meserve of

the New Hampshire regiment. He had been a ship-builder and his

knowledge of such work now served a good purpose, for he ordered

built rude sledges of heavy timbers and on these we placed the

guns. We had no oxen or horses to haul the sledges, nor would

they have been of much help for they also would have sunk in the

spongy soil. So we formed great teams of two hundred each, and,

harnessed to the sledges with rope and breast-straps and traces,

we dragged the guns along, wading to our knees in the muck. In

this manner with prodigious labor we got the guns into place and

in four days or rather nights, for we had to work under cover of

darkness to escape the French cannon balls, a battery of six

guns was planted on Green Hill and began at once to return the

French fire.

"As all other means had failed, it was

decided to try a midnight attack. Four hundred men under Captain

Brooks, on the night of May twenty-sixth, put off in boats from

the Royal Battery and nearly reached the island before they were

discovered by the French. At once shot and shell fell upon the

boats as the guns of the French battery were turned on them.

Although some of our men reached the island and made a dash for

the works with scaling ladders, they were driven back by the

terrific fire of the enemy and many were killed. Others were

driven into the sea and drowned, but the largest number were

made prisoners, only a few returning safely to the Royal

Battery. This was our severest loss of the siege and proved that

the Island Battery could not be captured by a sortie. So another

plan was tried.

"At the right of the harbor entrance

just opposite the Island Battery and only half a mile distant, a

new battery was planted under command of Colonel Gridley. As

this point was too far from camp to drag the guns by the team

method, it was necessary to take them around by boat, then hoist

them up the steep, rough cliffs and so get them into position.

By June fourteenth six guns were ready, and at noon, they joined

with all our other guns in a salute in honor of King George,

that day being the anniversary of his accession to the throne.

"On the day following Commodore Warren

came ashore for a council with General Pepperrell and his

officers. It was planned by them to make a combined attack upon

the fortress; the fleet coming into harbor and bombarding while

our forces attacked from the land. Just as Sir Peter was about

to return to his flagship, Duchambon, the French commander, sent

out a messenger under flag of truce, asking for suspension of

hostilities and terms of surrender.

"On May seventh, when the siege had but

begun, Pepperrell and Warren had sent Duchambon a summons to

surrender. He had replied that his king had confided the command

of the fortress to him and his only reply must be by the mouth

of his cannon. Now, however, he was ready to surrender for the

French were in a perilous condition. The accurate and incessant

fire of our guns had wrought appalling destruction to the walls

and gates of the fortress. The town was a ruin. Reinforcements

from Canada had not arrived and the ships sent from France with

supplies of food and ammunition had been captured by our

cruisers. Sensing all this the French could do naught but

capitulate, accepting the terms offered by our commanders w4io

assured them of 'humane and generous treatment.'

"That was a happy day for us you may be

sure, and a proud one, too, for we had accomplished that which

the French had considered impossible. In six weeks the strongest

fortifications in America had fallen, not to veterans with

trained leaders, but to a small force of raw, provincial militia

commanded by a merchant. Yes, our victory was complete. No

longer could Louisburg shelter our enemies or endanger our

liberties.

"King George showed his appreciation of

Pepperrell's services by creating him a Baronet of Great

Britain, and of Warren's services by making him a Rear Admiral.

Later Pepperrell and Governor Shirley were made Colonels in the

British Army, though never called into active service."

When Morris 'Brien finished his story he

arose and took from the high shelf over the fireplace the only

relic of the siege that he had brought back from Louisburg. This

was a brass mortar and pestle which some French housewife had

left in her hasty departure from the town.

Perhaps listening to this story made the

'Brien boys brave and daring, for after the family had moved to

Machias and Jerry and Gideon had become young men, they were

leaders in the capture of the British cutter "Margaretta" in

Machias Bay, June 12, 1775, the first naval battle of the

Revolution.

Beulah Sylvester Oxton

|

![]()

![]()