Sebastian Rale

Long ago, when the Abenaki roamed the

forests of Maine, there occurred in the Indian village of

Narrantsouk or Norridgewock, events so tragic that poet and

historian alike have told the tale for future generations. The

village, seventy-five miles from the mouth of the Kennebec, was

for the time and the race, rather pretentious. It consisted of a

square enclosure, 160 feet on each side, walled in by a palisade

of stout logs, nine feet in height. In the middle of each side

was a gate, and the two streets connecting these gates met in an

open square in the centre. Within this enclosure, on either side

of the two streets, were twenty-six wigwams, really huts, built

of round, hewn logs, "after the English manner." Outside, only a

few yards away, stood the chapel. It was of hewn timber,

surmounted by a cross. The bell of that ancient church is still

in existence, in the rooms of the Maine Historical Society,

Portland. Within, the rough chapel walls were hung with

pictures, among them the Crucifixion. The communion service was

of silver plate. We ask why so much of order and even of beauty

should be found in an Indian village in the forests of Maine.

But for thirty-four years, these Indians had been taught by

Father Sebastian Rale, a Jesuit priest. Whittier describes the

scene most effectively.

"On the brow of a hill which slopes to

meet

The flowing river and bathe its feet.

The bare-washed and drooping grass

And the creeping vine, as the waters pass,

A rude, unshapely chapel stands.

Built up in that wild by unskillful hands;

Yet the traveler knows it's a place of prayer,

For the holy sign of the cross is there;

And should he chance at that place to be,

Of a Sabbath morn or some hallowed day,

When prayers are made and masses said.

Some for the living and some for the dead,

Well might that traveler start to see

The tall, dark forms that take their way

From the birch canoe on the river shore

And the forest paths to that chapel door;

And marvel to mark the naked knees

And the dusky foreheads bending there,

And, stretching his long, thin arms over these

In blessing and in prayer.

Like a shrouded specter, pale and tall.

In his coarse white vesture. Father Rale.

To add to the effectiveness of the

service, a choir, gowned and trained, had been formed of forty

of the braves. At dawn and again for vespers, the bell rang to

summon these dusky worshipers to prayers.

Father Rale, pastor of this unusual

flock, was a Jesuit priest who had come to Canada with

Frontenac. He was of illustrious French family, and finely

educated; but he was content to give up all that he might have

enjoyed in France, and to suffer hardship unspeakable in order

to teach the precepts of religion to the Indians of the New

World.

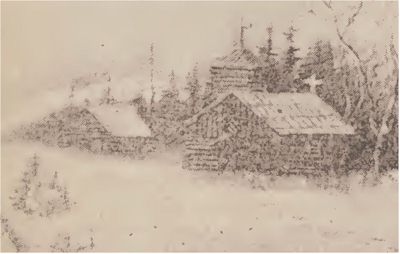

|

Father Rale's Chapel

(By Courtesy of John Francis Sprague Author of Sebastian

Rale.) |

In the Abenaki village to which he was

finally assigned, all of Rale's various acquirements were of

use. He was carpenter, gardener, and physician, as well as

priest. Nor was he less the scholar. Ho prepared a vocabulary of

the Abenaki tongue that is now preserved in the Library of

Harvard College, and he was at work on an Indian dictionary at

the time of his tragic death.

But not all of Father Rale's activities

met the approval of his English neighbors. For one thing, the

French claimed the Kennebec as their western boundary, while the

English insisted on a river which we call the St. John, the

present boundary between Maine and the Dominion of Canada. They

declared that Rale and his Indians were trespassers on English

soil. But they accused Rale also of something worse than simple

trespass. They declared that he was guilty of inciting the

Indians to attack the English settlements. It was in that period

of bitter feeling known to us as the French and Indian Wars,

and, as we know, the Indians of Maine had been merciless in

their attacks, both with and without their allies, the French.

Small wonder that feeling in Massachusetts ran high and a price

was set upon Rale's head. Just how far these attacks were due to

Rale, history has not decided. Certain it is that the priest did

translate and forward to the Governor of Massachusetts the

Abenaki's declaration of their right, as first settlers, to the

land they dwelt upon and hunted over.

In 1723, matters came to a crisis. After

a series of blood-thirsty raids by the Indians, an expedition

under the leadership of Captain Moulton of York was sent to

Norridgewock to seize the hitherto elusive priest. This

expedition failed in making the capture. Though the English

surprised the Indian village, Rale escaped, and the only trophy

Moulton could bring back was the priest's strong box. This

contained, among other papers, correspondence with the Governor

of Canada that showed Rale to be to some extent responsible for

the outbreaks against the English. Doubtless Rale thought

himself justified, because of the possible peril to his mission

at the hands of the English Puritans.

In August, 1724, a second expedition,

commanded by Captains Moulton and Harmon, ascended the river. On

the way they saw three Indians and shot at them. One, who proved

to be the noted chieftain, Bombassen, was killed; the other two,

his wife and daughter, were taken prisoners.

''Bomazon from Tacconock

Has sent his runners to Norridgewock,

With tidings that Moulton and Harmon of York

Far up the river have come;

They have left their boats - they have entered the wood,

And filled the depths of the solitude

With the sound of the ranger's drum."

So wrote the poet Whittier of their

approach. But, in actual fact, so silent and swift was the

advance, due to information extorted from the captive wife of

Bombassen, that the Indian village was surrounded and surprised.

At the first volley, the Indians rushed

from their wigwams, fired, but too high, and fell in confusion

before the better aimed English bullets. No more than sixty

warriors were in the village at this time. These, in spite of

the odds, for the English force is variously estimated at from

two hundred and eighty to eleven hundred, did their best to the

last to cover the retreat of the old men, the women and

children. Many of these were caught in the river, as they

attempted to cross, and were slaughtered.

Rale fearlessly presented himself to his

assailants, hoping to gain some measure of protection for his

people, but in vain. He fell, shot through the head, and the few

braves who had endeavored to protect him shared his fate. Among

the slain was Mogg, an old and famous chieftain. The rangers

burned and plundered, then retreated down the valley with their

burden of scalps.

Father Rale's mutilated body was

tenderly buried by the remnant of his sorrowing people; but the

strength of the Norridgewocks was broken. The few survivors of

the tribe sought other hunting grounds, and Narrantsouk was left

desolate.

"No wigwam's smoke is curling there;

The very earth is scorched and bare,

They pass and listen to catch a sound

Of breathing life, but there comes not one,

Save the foxes' bark and the rabbit's bound."

In 1833, a monument was erected to the

memory of Father Rale on the site of the chapel where he had

ministered to his savage converts. It consists of a granite

shaft, eleven feet high, on a base five feet in height. The

whole is surmounted by an iron cross. On one side an inscription

is cut in Latin. Translated, it reads:

''Rev. Sebastian Rale, a French Jesuit

missionary, for many years the first evangelist among the

Illinois and Hurons, and afterwards for thirty-four years a true

apostle in the faith and love of Christ, among the Abenakis,

un-terrified by danger, and often by his pure excellent

character giving witness that he was prepared for death, this

most excellent pastor, on the 23d day of August, 1724, fell in

this place, at the time of the destruction and slaughter of the

town of Norridgewock, and the dangers to his church. To him, and

to his children, dead in Christ, Benedict Fenwick, Bishop at

Boston, has erected and dedicated this monument, this 23d day of

August, A.D. 1833.''

Henrietta Tozier Totman

|

![]()

![]()