The Voyage of the Archangel

On a pleasant day in May, 1605, more

than three centuries ago, a white-winged ship came to anchor off

the rocky shores of the island now known as Monhegan. It was the

Archangel, commanded by George Weymouth, forty-five days out

from England.

Fuel and water being scarce upon the

ship, Weymouth, with several of his men, went on shore to

procure these necessaries. "Mayhap we shall see some of the

savage people whom others have seen on these shores,'' said one

of the men as they neared the coast. No trace of human

habitation could be seen. Where now may be found the gray

fish-houses, piles of lobster-traps, neat cottages, and the

great light-house standing over all like a lone sentinel which

never sleeps, then were only great, gray rocks half hidden

beneath riotous masses of wild rose and yew, and an unbroken

stretch of primeval forest.

When the Englishmen had obtained wood

and water sufficient for their needs, they made their way toward

the shore. Suddenly one of them stopped near a pile of loose

stones. "What have we here?" he cried. "Look! these are the

ashes and charred remains of a fire. Those who built it must

have fled at our approach.''

All eyes eagerly scanned the landscape,

but no unfamiliar face or form appeared. Amid the screaming of

seagulls, they planted a cross, naming the island St. George,

then rowed back to the Archangel.

The Archangel remained at her anchorage

that night, and on the following day, because the vessel ''rode

too much open to the sea and winds,'' Weymouth weighed anchor

and brought his vessel to the other islands nearer the mainland

in the direction of the mountains.

With great interest Weymouth and his

crew landed upon one of the islands (probably what is now known

as Allen's Island, in St. Georges Harbor.) Very soon a discovery

was made by the mate, Thomas Cam, which brought all around him.

"Here has been a fire!" he exclaimed, "and see the great shells

lying all about! " Pieces of large shells and bones littered the

ground; evidently a feast had been held there not long ago. A

careful search, however, failed to reveal any further trace of

human beings.

The next week furnished plenty of work;

the building of the shallop went speedily forward. The

neighboring islands were explored. On the twenty-ninth of May,

the shallop was finished and, leaving fourteen men on the

Archangel, Captain Weymouth, with, thirteen others, started on

an exploring expedition inland.

"There does not seem to be much treasure

on these islands," said Thomas Cam to one of his comrades, Owen

Griffith, as they gazed from the side of the ship over the

island dotted expanse of water which Weymouth, because of the

season, had called Pentecost Harbor.

"Neither of treasure nor of people have

I had a sight,'' replied the man Griffith, "and yet the fires

would show the land to be inhabited. Perhaps the sight of our

goodly ship has filled them with fear, so that they flee from

us."

"Tis a noble land in which the king may

build a powerful empire," said the other, "and mightily enrich

himself in so doing." Suddenly he stopped, shading his eyes with

his hand. "Ha, Master Griffith," he cried, "at least one wish is

about to be gratified; yonder come three canoes filled with

savages!"

With excited shouts the crew lined the

side of the vessel, watching eagerly while the savages landed on

an island opposite, staring in wonder at the strange vision of

the white-sailed ship and the white-faced, bearded men who stood

upon its deck. Presently, in answer to the inviting gestures of

the white man, a canoe in which were three natives was paddled

boldly toward the ship. As they came alongside one raised an oar

and pointed fiercely toward the open sea, at the same time

exclaiming loudly in a harsh, unknown tongue.

"They do not seem to like our company,"

said the mate, "tis a pity we can not speak their language. Show

them some knives and glasses and the rings and other trinkets we

have with us."

These were quickly brought and displayed

to the delighted eyes of the natives who brought their frail

canoe still nearer to see these wonderful toys at closer range.

It was now but an easy step to induce the three to climb over

the side of the Archangel. Sounds of wonder and delight burst

from them as they wandered freely about the vessel, one even

venturing below. Food was offered them and they gladly ate the

cooked, but the raw disgusted them. They hung joyously over a

collection of combs, kettles and armor, but the sight and sound

of the matchlocks filled them with unmeasured fear.

It was with equal surprise and pleasure that the Englishmen

gazed at their strange visitors, representatives of this vast

New World. They were well formed, of medium build, bodies

painted black, faces red or blue and eyebrows white, and clothed

in mantles and moccasins of deerskin. By signs the white men

told them that they wished to trade knives and trinkets for

furs, which seemed to satisfy the savages and with many a

backward glance they at last took their departure.

About ten o'clock the shallop bearing

Capt. Weymouth returned. He bore the news of the discovery of a

great river and the stories which each party had to relate were

heard with eager interest.

"Tomorrow," said Capt. Weymouth, "We

will go on shore and trade. Let us do nothing to frighten these

savages who seem peaceable enough."

This plan of trade was carried out. The

natives were delighted to exchange beaver and otter skins for

worthless trinkets, and now wholly without fear crowded closely

about the white strangers. Presents were brought of tobacco, of

which these natives cultivated small quantities and smoked it in

pipes made of lobster claws.

"Let us show them some wonders,'' said

Weymouth, and, with the point of his sword previously touched by

a magnet, he picked up a knife holding it high in the air. The

wonder of the savages was intense. Presently one of the boldest

seized the knife and drew it away, then hastily dropped it as if

fearful of coming to harm. Holding the sword point close,

Weymouth caused the knife to turn in different directions; the

same bold native tried to imitate the act with his bone-headed

dart, but failure of course resulted.

"Let us try to get some of them to go

back to the ship with us," said the mate to Weymouth. "Those who

came yesterday went away much pleased and others will doubtless

hold it a high honor."

The captain agreed and with very little

urging two of the natives entered the shallop and the crew

returned to the Archangel. As they sprang upon the deck one of

the ship's dogs ran forward sniffing and barking furiously. With

every sign of fear, the natives turned and seemed about to fling

themselves into the sea.

"Tie those dogs!" roared Weymouth, then

with kind tones and gestures reassured his dusky guests until

their confidence returned and they wandered as freely over the

ship as the visitors of the day before. Of the food offered

them, peas seemed to please them most. By signs they expressed a

wish to carry some back to their friends, and a quantity was

given them in a metal dish which they returned later with great

care. At their departure others came and finally three were

persuaded to remain on board all night, one of the white men

being left on shore as a sort of guarantee of good faith,

although the trust of the Indians was so great that none was

needed.

That night Weymouth stood in' the soft

June starlight and gazed on the dark forms of the sleeping

savages as they lay on the deck covered with an old sail. "How

great would be the pleasure of the king and certain noble gentry

of England to behold these strange people," he thought. "They

are ever interested in tales of this great New World.'' Then of

a sudden he smote his palms softly together and turned sharply

to Thomas Cam who stood near. "Cam!'' he said, "what say ye,

shall we take some of these knaves with us when the Archangel

turns her prow toward England? What easier task, see how the

poor fools trust us!" and he gave a half contemptuous laugh.

The mate whistled softly in his beard. "Twould

surely bring us great notice and reward," he said at last. ''His

majesty ever listens eagerly to adventurers from over seas, and

'twere easy enough to be done; yet," he spoke hesitatingly, ''it

seems but a poor return and not half honorable."

"What know they of honor," cried

Weymouth impatiently, "they are but beasts. Canst talk of honor

with a dog! Be sensible, man, and think of the great good we may

give our countrymen by thus turning their eyes to this new

land."

"Tis doubtless as you say," replied Cam, beginning to yield,

"yet methinks even a dog knows gratitude and will repay

treachery. However, if you wish it, we are bound to obey your

commands, and perchance no harm will come of it."

At this point one of the savages stirred in his sleep and tossed

a dusky arm above his head.

"Tis as if he held a weapon ready to

strike!" muttered Cam drawing back a step.

"Away with such fears!" cried Weymouth

striking his comrade a resounding blow between the shoulders.

"What spirit is this for discoverers in unknown worlds! Come,

let us discuss the plan."

A week later the Archangel had completed

her work and had shipped a large quantity of furs. The thoughts

of all now turned homeward. One afternoon two canoes with three

Indians visited the ship, while two other savages remained on

the shore of a nearby island seated by a fire built on the

rocks.

"This is our chance," said Weymouth to

his men. "Get some of them to go below and do not allow them to

come back on deck."

Two painted faces at that moment

appeared over the side of the vessel. Griffith walked up to them

with a pleasant smile. "Come below with me," he said, "I have

something new to show you." The simple natives understood his

signs but not his words and readily followed him below. The

others would not leave their canoes. A plate of peas was passed

down to them which they received with exclamations of pleasure

and hurried to the island to share the dainty with their

relatives. The peas were rapidly eaten and a young savage,

seizing a pewter plate, leaped into a canoe and returned to the

ship, joining the others below where he found himself a

prisoner. Three other savages were now held captive on the

Archangel. As this number did not satisfy Weymouth, the shallop

with eight men was sent to the shore as if to trade.

At their approach three of the natives

retired to the woods, but the other two advanced and received

the proffered gifts of some combs and another plate of their

favorite eatable. All made their way over the rocks and seaweed

and sat down around the fire.

|

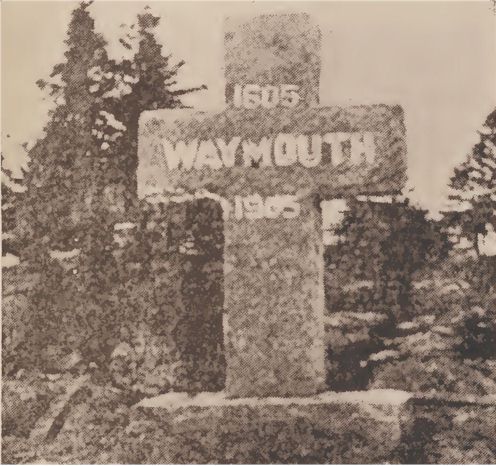

Cross on Allen's Island

Erected on 300th Anniversary of Weymouth's Visit

|

Never had the white men been more

courteous and peaceful in their behavior; never had the simple

natives showed more fully their gratitude and trust. Then as

suddenly as the tiger springs upon its prey did the treacherous

Europeans fall upon their unsuspecting hosts. As fear rushed in

to take the place of confidence, it required the strength of all

the eight to hold the slippery, struggling bodies of their

captives and bear them to the boat.

In high spirits Weymouth greeted the

return of the crew. "This will be enough," he said. "Take them

below with their comrades. I have just learned that one of them

is a special prize, a chieftain named Nahanada. Now we will go

home.''

With despairing hearts these victims of Weymouth's treachery

were dragged from the deck of the Archangel never expecting to

behold their native shores again. How little could they imagine

the strange life which for the next three years was to be

theirs; to be transplanted to a foreign land and gazed at by the

curious eyes of a great metropolis; then, when the new tongue

was mastered, to relate to the wondering ear of royalty the

story of a mighty land with its unbounded riches of sea and

shore; and finally to be restored to their own people to act as

guides to future voyagers!

Note. - Some authorities hold that the mountains seen by

Weymouth, or Waymouth, as his name is often spelled, were the

White Mountains and that the harbor into which he sailed was

Boothbay and the river, the Kennebec. The White Mountains,

however, are seen from Monhegan only under the most favorable

conditions. There seems little doubt that the mountains were the

Camden Hills, and the islands which the Weymouth party explored

after leaving Monhegan were the islands in George's Harbor, near

Thomaston, including Allen's and Burnt Island.

In July, 1905, the Maine Historical

Society celebrated the tercentenary of Weymouth's voyage, and on

Allen's Island erected and dedicated a memorial cross.

Could Weymouth have foreseen the acts of

bitter revenge which were to be heaped upon the heads of the

innocent as well as the guilty as the result of this unfriendly

deed, perhaps he would have repented and released his captives

to return to their forest homes. But repentance was now too

late, the Archangel was swiftly cleaving her way through the

blue waters toward the longed for shores of old England.

Thus was committed, near the magnificent

harbor of St. Georges, the deed which was to cause the Indians

to regard all Englishmen with hatred and distrust; and was to

turn the attention of all England to the splendor and riches of

the coast of Maine.

Charlotte M. H. Beath

|

![]()

![]()